On teaching developmental biology and trying to decide where to start: differentiation

Having considered the content of courses in chemistry [1] and biology [2, 3], and preparing to teach developmental biology for the first time, I find myself reflecting on how such courses might be better organized. In my department, developmental biology (DEVO) has returned after a hiatus as the final capstone course in our required course sequence, and so offers an opportunity within which to examine what students have mastered as they head into their more specialized (personal) educational choices. Rather than describe the design of the course that I will be teaching, since at this point I am not completely sure what will emerge, what I intend to do (in a series of posts) is to describe, topic by topic, the progression of key concepts, the observations upon which they are based, and the logic behind their inclusion.

Modern developmental biology emerged during the mid-1800s from comparative embryology [4] and was shaped by the new cell theory (the continuity of life and the fact that all organisms are composed of cells and their products) and the ability of cells to differentiate, that is, to adopt different structures and behaviors [5]. Evolutionary theory was also key. The role of genetic variation based on mutations and selection, in the generation of divergent species from common ancestors, explained why a single, inter-connected Linnaean (hierarchical) classification system (the phylogenic tree of life →) of organisms was possible and suggested that developmental mechanisms were related to similar processes found in their various ancestors.

So then, what exactly are the primary concepts behind developmental biology and how do they emerge from evolutionary, cell, and molecular biology? The concept of “development” applies to any process characterized by directional changes over time. The simplest such process would involve the progress from the end of one cell division event to the beginning of the next; cell division events provide a convenient benchmark. In asexual species, the process is clonal, a single parent gives rise to a genetically identical (except for the occurrence of new mutations) offspring. Often there is little distinction between parent and offspring. In sexual species, a dramatic and unambiguous benchmark involves the generation of a new and genetically distinct organism. This “birth” event is marked by the fusion of two gametes (fertilization) to form a new diploid organism. Typically gametes are produced by a complex cellular differentiation process (gametogenesis), ending with meiosis and the formation of haploid cells. In multicellular organisms, it is often the case that a specific lineage of cells (which reproduce asexually), known as the germ line, produce the gametes. The rest of the organism, the cells that do not produce gametes, is known as the soma, composed of somatic cells. Cellular continuity remains, however, since gametes are living (albeit haploid) cells.

It is common for the gametes that fuse to be of two different types, termed oocyte and sperm. The larger, and generally immotile gamete type is called an oocyte and an individual that produces oocytes is termed female. The smaller, and generally motile gamete type is called a sperm; individuals that produces sperm are termed male. Where a single organism can produce both oocytes and sperm, either at the same time or sequentially, they are referred to as hermaphrodites (named after Greek Gods, the male Hermes and the female Aphrodite). Oocytes and sperm are specialized cells; their formation involves the differential expression of genes and the specific molecular mechanisms that generate the features characteristic of the two cell types. The fusion of gametes, fertilization, leads to a zygote, a diploid cell that (usually) develops into a new, sexually mature organism.

An important feature of the process of fertilization is that it requires a level of social interaction, the two fusing cells (gametes) must recognize and fuse with one another. The organisms that produce these gametes must cooperate; they need to produce gametes at the appropriate time and deliver them in such a way that they can find and recognize each other and avoid “inappropriate” interactions”. The specificity of such interactions underlie the reproductive isolation that distinguishes one species from another. The development of reproductive isolation emerges as an ancestral population of organisms diverges to form one or more new species. As we will see, social interactions, and subsequent evolutionary effects, are common in the biological world.

The cellular and molecular aspects of development involve the processes by which cells grow, replicate their genetic material (DNA replication), divide to form distinct parent-offspring or similar sibling cells, and may alter their morphology (shape), internal organization, motility, and other behaviors, such as the synthesis and secretion of various molecules, and how these cells respond to molecules released by other cells. Developmental processes involve the expression and the control of all of these processes.

Essentially all changes in cellular behavior are associated with changes in the activities of biological molecules and the expression of genes, initiated in response to various external signaling events – fertilization itself is such a signal. These signals set off a cascade of regulatory interactions, often leading to multiple “cell types”, specialized for specific functions (such as muscle contraction, neural and/or hormonal signaling, nutrient transport, processing, and synthesis, etc.). For specific parts of the organism, external or internal signals can result in a short term “adaptive” response (such as sweating or panting in response to increased internal body temperature), after which the system returns to its original state, or in the case of developing systems, to new states, characterized by stable changes in gene expression, cellular morphology, and behavior.

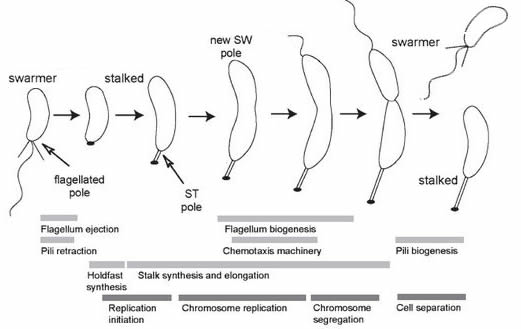

Development in bacteria (and other unicellular organisms): In most unicellular organisms, the cell division process is reasonably uneventful, the cells produced are similar to the original cell – but not always. A well studied example is the bacterium Caulobacter crescentus (and related species) [link][link]. In cases such as this, the process of growth leads to phenotypically different daughters. While it makes no sense to talk about a beginning (given the continuity of life after the appearance of the last universal common ancestor or LUCA), we can start with a “swarmer” cell, characterized by the presence of a motile flagellum (a molecular machine driven by coupled chemical reactions – see past blogpost] that drives motility [figure modified from 6 ↓].

A swarmer will eventually settle down, loose the flagellum, and replace it with a specialized structure (a holdfast) designed to anchor the cell to a solid substrate. As the organism grows, the holdfast develops a stalk that lifts the cell away from the substrate. As growth continues, the end of the cell opposite the holdfast begins to differentiate (becomes different) from the holdfast end of the cell – it begins the process leading to the assembly of a new flagellar apparatus. When reproduction (cell growth, DNA replication, and cell division) occurs, a swarmer cell is released and can swim away and colonize another area, or settle nearby. The holdfast-anchored cell continues to grow, producing new swarmers. This process is based on the inherent asymmetry of the system – the holdfast end of the cell is molecularly distinct from the flagellar end [see 7].

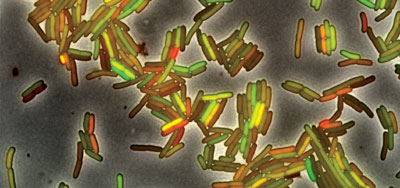

The process of swarmer cell formation in Caulobacter is an example of what we will term deterministic phenotypic switching. Cells can also exploit molecular level noise (stochastic processes) that influence gene expression to generate phenotypic heterogeneity, different behaviors expressed by genetically identical cells within the same environment [see 8, 9]. Molecular noise arises from the random nature of molecular movements and the rather small (compared to macroscopic systems) numbers of most molecules within a cell. Most cells contain one or two copies of any particular gene, and a similarly small number of molecular sequences involved in their regulation [10]. Which molecules are bound to which regulatory sequence, and for how long, is governed by inter-molecular surface interactions and thermally driven collisions, and is inherently noisy. There are strategies that can suppress but not eliminate such noise [see 11]. As dramatically illustrated by Elowitz and colleagues [8](↑), molecular level noise can produce cells with different phenotypes. Similar processes are active in eukaryotes (including humans), and can lead to the expression of one of the two copies of a gene (mono-allelic expression) present in a diploid organism. This can lead to effects such as haploinsufficiency and selective (evolutionary) lineage effects if the two alleles are not identical [12, 13]. Such phenotypic heterogeneity among what are often genetically identical cells is a topic that is rarely discussed (as far as I can discern) in introductory cell, molecular, or developmental biology courses [past blogpost].

The ability to switch phenotypes can be a valuable trait if an organism’s environment is subject to significant changes. As an example, when the environment gets hostile, some bacterial cells transition from a rapidly dividing to a slow or non-dividing state. Such “spores” can differentiate so as to render them highly resistant to dehydration and other stresses. If changes in environment are very rapid, a population can protect itself by continually having some cells (stochastically) differentiating into spores, while others continue to divide rapidly. Only a few individuals (spores) need to survive a catastrophic environmental change to quickly re-establish the population.

Dying for others – social interactions between “unicellular” organisms: Many students might not predict that one bacterial cell would “sacrifice” itself for the well being of others, but in fact there are a number of examples of this type of self-sacrificing behavior, known as programmed cell death, which is often a stochastic process. An interesting example is provided by cellular specialization for photosynthesis or nitrogen fixation in cyanobacteria [see 9]. These two functions require mutually exclusive cellular environments to occur, in particular the molecular oxygen (O2) released by photosynthesis inhibits the process of nitrogen fixation. Nevertheless, both are required for optimal growth. The solution? some cells differentiate into what are known as heterocysts, cells committed to nitrogen fixation (← a heterocyst in Anabaena spiroides, adapted from link), while most ”vegetative” cells continue with photosynthesis. Heterocysts cannot divide, and eventually die – they sacrifice themselves for the benefit of their neighbors, the vegetative cells, cells that can reproduce.

The process by which the death of an individual can contribute resources that can be used to insure or enhance the survival and reproduction of surrounding individuals is an inherently social process, and is subject of social evolutionary mechanisms [14, 15][past blogpost]. Social behaviors can be selected for because the organism’s neighbors, the beneficiaries of their self-sacrifice are likely to be closely (clonally) related to themselves. One result of the social behavior is, at the population level, an increase in one aspect of evolutionary fitness, termed “inclusive fitness.”

Such social behaviors can enable a subset of the population to survive various forms of environmental stress (see spore formation above). An obvious environmental stress involves the impact of viral infection. Recall that viruses are completely dependent upon the metabolic machinery of the infected cell to replicate. While there are a number of viral strategies, a common one is bacterial lysis – the virus replicates explosively, kills the infected cells, leading to the release of virus into the environment to infect others. But, what if the infected cell kills itself BEFORE the virus replicates – the dying (self-sacrificing, altruistic) cell “kills” the virus (although viruses are not really alive) and stops the spread of the infection. Typically such genetically programmed cell death responses are based on a simple two-part system, involving a long lived toxin and a short-lived anti-toxin. When the cell is stressed, for example early during viral infection, the level of the anti-toxin can fall, leading to the activation of the toxin.

Other types of social behavior and community coordination (quorum effects): Some types of behaviors only make sense when the density of organisms rises above a certain critical level. For example, it would make no sense for an Anabaena cell to differentiate into a heterocyst (see above) if there are no vegetative cells nearby. Similarly, there are processes in which a behavior of a single bacterial cell, such as the synthesis and secretion of a specific enzyme, a specific import or export machine, or the construction of a complex, such as a DNA uptake machine, makes no sense in isolation – the secreted molecule will just diffuse away, and so be ineffective, the molecule to be imported (e.g. lactose) or exported (an antibiotic) may not be present, or there may be no free DNA to import. However, as the concentration (organisms per volume) of bacteria increases, these behaviors can begin to make biological sense – there is DNA to eat or incorporate and the concentration of secreted enzyme can be high enough to degrade the target molecules (so they are inactivated or can be imported as food).

So how does a bacterium determine whether it has neighbors or whether it wants to join a community of similar organisms? After all, it does not have eyes to see. The process used is known as quorum sensing. Each individual synthesizes and secretes a signaling molecule and a receptor protein whose activity is regulated by the binding of the signaling molecule. Species specificity in signaling molecules and receptors insures that organisms of the same kind are talking to one another and not to other, distinct types of organisms that may be in the environment. At low signaling molecule concentrations, such as those produced by a single bacterium in isolation, the receptor is not activated and the cell’s behavior remains unchanged. However, as the concentration of bacteria increases, the concentration of the signal increases, leading to receptor activation. Activation of the receptor can have a number of effects, including increased synthesis of the signal and other changes, such as movement in response to signals through regulation of flagellar and other motility systems, such a system can lead to the directed migration (aggregation) of cells [see 16].

In addition to driving the synthesis of a common good (such as a useful extracellular molecule), social interactions can control processes such as programmed cell death. When the concentration of related neighbors is high, the programmed death of an individual can be beneficial, it can lead to release of nutrients (common goods, including DNA molecules) that can be used by neighbors (relatives)[17, 18] – an increase in the probability of cell death in response to a quorum can increased in a way that increases inclusive fitness. On the other hand, if there are few related individuals in the neighborhood, programmed cell death “wastes” these resources, and so is likely to be suppressed (you might be able to generate a plausible mechanism that could control the probability of programmed cell death).

As we mentioned previously with respect to spore formation, the generation of a certain percentage of “persisters” – individuals that withdraw from active growth and cell division, can enable a population to survive stressful situations, such as the presence of an antibiotic. On the other hand, generating too many persisters may place the population at a reproductive disadvantage. Once the antibiotic is gone, the persisters can return into active division. The ability of bacteria to generate persisters is a serious problem in treating people with infections, particularly those who stop taking their antibiotics too early [19].

Of course, as in any social system, the presumption of cooperation (expending energy to synthesize the signal, sacrificing oneself for others) can open the system to cheaters [blogpost]. All such “altruistic” behaviors are vulnerable to cheaters.* For example, a cheater that avoids programmed cell death (for example due to an inactivating mutation that effects the toxin molecule involved) will come to take over the population. The downside, for the population, is that if cheaters take over, the population is less likely to survive the environmental events that the social behavior was evolve to address. In response to the realities of cheating, social organisms adopt various social-validation and policing systems [see 20 as an example]; we see this pattern of social cooperation, cheating, and social defense mechanism throughout the biological world.

Follow-on posts:

footnotes:

* Such as people who fail to pay their taxes or disclose their tax returns.

literature cited:

1. Cooper, M.M. and M.W. Klymkowsky, Chemistry, life, the universe, and everything: a new approach to general chemistry, and a model for curriculum reform. J. Chem. Educ. 2013. 90: 1116-1122 & Cooper, M. M., R. Stowe, O. Crandell and M. W. Klymkowsky. Organic Chemistry, Life, the Universe and Everything (OCLUE): A Transformed Organic Chemistry Curriculum. J. Chem. Educ. 2019. 96: 1858-1872.

2. Klymkowsky, M.W., Teaching without a textbook: strategies to focus learning on fundamental concepts and scientific process. CBE Life Sci Educ, 2007. 6: 190-3.

3. Klymkowsky, M.W., J.D. Rentsch, E. Begovic, and M.M. Cooper, The design and transformation of Biofundamentals: a non-survey introductory evolutionary and molecular biology course. LSE Cell Biol Edu, 2016. pii: ar70.

4. Arthur, W., The emerging conceptual framework of evolutionary developmental biology. Nature, 2002. 415: 757.

5. Wilson, E.B., The cell in development and heredity. 1940.

6. Jacobs‐Wagner, C., Regulatory proteins with a sense of direction: cell cycle signalling network in Caulobacter. Molecular microbiology, 2004. 51:7-13.

7. Hughes, V., C. Jiang, and Y. Brun, Caulobacter crescentus. Current biology: CB, 2012. 22:R507.

8. Elowitz, M.B., A.J. Levine, E.D. Siggia, and P.S. Swain, Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science, 2002. 297:1183-6.

9. Balázsi, G., A. van Oudenaarden, and J.J. Collins, Cellular decision making and biological noise: from microbes to mammals. Cell, 2011. 144: 910-925.

10. Fedoroff, N. and W. Fontana, Small numbers of big molecules. Science, 2002. 297:1129-1131.

11. Lestas, I., G. Vinnicombe, and J. Paulsson, Fundamental limits on the suppression of molecular fluctuations. Nature, 2010. 467:174-178.

12. Zakharova, I.S., A.I. Shevchenko, and S.M. Zakian, Monoallelic gene expression in mammals. Chromosoma, 2009. 118:279-290.

13. Deng, Q., D. Ramsköld, B. Reinius, and R. Sandberg, Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic, random monoallelic gene expression in mammalian cells. Science, 2014. 343: 193-196.

14. West, S.A., A.S. Griffin, A. Gardner, and S.P. Diggle, Social evolution theory for microorganisms. Nature reviews microbiology, 2006. 4:597.

15. Bourke, A.F.G., Principles of Social Evolution. Oxford series in ecology and evolution. 2011, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

16. Park, S., P.M. Wolanin, E.A. Yuzbashyan, P. Silberzan, J.B. Stock, and R.H. Austin, Motion to form a quorum. Science, 2003. 301:188-188.

17. West, S.A., S.P. Diggle, A. Buckling, A. Gardner, and A.S. Griffin, The social lives of microbes. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2007: 53-77.

18. Durand, P.M. and G. Ramsey, The Nature of Programmed Cell Death. Biological Theory, 2018: 1-12.

19. Fisher, R.A., B. Gollan, and S. Helaine, Persistent bacterial infections and persister cells. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2017. 15:453.

20. Queller, D.C., E. Ponte, S. Bozzaro, and J.E. Strassmann, Single-gene greenbeard effects in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Science, 2003. 299: 105-106.

second factor, independent of whether the term race has any useful scientific purpose, namely to help students understand the biological (evolutionary) origins of racism itself, together with the stressors that lead to its periodic re-emergence as a socio-political factor. In times of social stress, reactions to strangers (others) identified by variations in skin color or overt religious or cultural signs (dress), can provoke hostility against those perceived to be members of a different social group.

second factor, independent of whether the term race has any useful scientific purpose, namely to help students understand the biological (evolutionary) origins of racism itself, together with the stressors that lead to its periodic re-emergence as a socio-political factor. In times of social stress, reactions to strangers (others) identified by variations in skin color or overt religious or cultural signs (dress), can provoke hostility against those perceived to be members of a different social group.

people as disposable machines, to be sacrificed for some ideological or religious faith (3).

people as disposable machines, to be sacrificed for some ideological or religious faith (3). This is not to imply that humans (and other animals) are totally in control of their thoughts and actions, completely “free” – obviously not.

This is not to imply that humans (and other animals) are totally in control of their thoughts and actions, completely “free” – obviously not. making ~7,000,000,000,000,000 synapses with one another, and interacting in various ways with ~100,000,000,000 glia that include non-neuronal astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and immune system microglia (von Bartheld et al., 2016). These considerations ignore the recently discovered effects of the rest of the body (and its microbiome) on the brain (see Mayer et al., 2014; Smith, 2015).

making ~7,000,000,000,000,000 synapses with one another, and interacting in various ways with ~100,000,000,000 glia that include non-neuronal astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and immune system microglia (von Bartheld et al., 2016). These considerations ignore the recently discovered effects of the rest of the body (and its microbiome) on the brain (see Mayer et al., 2014; Smith, 2015).