Biological systems are characterized by the ubiquitous roles of weak, that is, non-covalent molecular interactions, small, often very small, numbers of specific molecules per cell, and Brownian motion. These combine to produce stochastic behaviors at all levels from the molecular and cellular to the behavioral. That said, students are rarely introduced to the ubiquitous role of stochastic processes in biological systems, and how they produce unpredictable behaviors. Here I present the case that they need to be and provide some suggestions as to how it might be approached.

Background: Three recent events combined to spur this reflection on stochasticity in biological systems, how it is taught, and why it matters. The first was an article describing an approach to introducing students to homeostatic processes in the context of the bacterial lac operon (Booth et al., 2022), an adaptive gene regulatory system controlled in part by stochastic events. The second were in-class student responses to the question, why do interacting molecules “come back apart” (dissociate). Finally, there is the increasing attention paid to what are presented as deterministic genetic factors, as illustrated by talk by Kathryn Harden, author of the “The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA matters for social equality” (Harden, 2021). Previous work has suggested that students, and perhaps some instructors, find the ubiquity, functional roles, and implications of stochastic, that is inherently unpredictable processes, difficult to recognize and apply. Given their practical and philosophical implications, it seems essential to introduce students to stochasticity early in their educational journey.

added 7 March 2023; Should have cited: You & Leu (2020).

What is stochasticity and why is it important for understanding biological systems? Stochasticity results when intrinsically unpredictable events, e.g. molecular collisions, impact the behavior of a system. There are a number of drivers of stochastic behaviors. Perhaps the most obvious, and certainly the most ubiquitous in biological systems is thermal motion. The many molecules within a solution (or a cell) are moving, they have kinetic energy – the energy of motion and mass. The exact momentum of each molecule cannot, however, be accurately and completely characterized without perturbing the system (echos of Heisenberg). Given the impossibility of completely characterizing the system, we are left uncertain as to the state of the system’s components, who is bound to whom, going forward.

Through collisions energy is exchanged between molecules. A number of chemical processes are driven by the energy delivered through such collisions. Think about a typical chemical reaction. In the course of the reaction, atoms are rearranged – bonds are broken (a process that requires energy) and bonds are formed (a process that releases energy). Many (most) of the chemical reactions that occur in biological systems require catalysts to bring their required activation energies into the range available within the cell. [1]

What makes the impact of thermal motion even more critical for biological systems is that many (most) regulatory interactions and macromolecular complexes, the molecular machines discussed by Alberts (1998) are based on relatively weak, non-covalent surface-surface interactions between or within molecules. Such interactions are central to most regulatory processes, from the activation of signaling pathways to the control of gene expression. The specificity and stability of these non-covalent interactions, which include those involved in determining the three-dimensional structure of macromolecules, are directly impacted by thermal motion, and so by temperature – one reason controlling body temperature is important.

So why are these interactions stochastic and why does it matter? A signature property of a stochastic process is that while it may be predictable when large numbers of atoms, molecules, or interactions are involved, the behaviors of individual atoms, molecules, and interactions are not. A classic example, arising from factors intrinsic to the atom, is the decay of radioactive isotopes. While the half-life of a large enough population of a radioactive isotope is well defined, when any particular atom will decay is, in current theory, unknowable, a concept difficult for students (see Hull and Hopf, 2020). This is the reason we cannot accurately predict whether Schrȍdinger’s cat is alive or dead. The same behavior applies to the binding of a regulatory protein to a specific site on a DNA molecule and its subsequent dissociation: predictable in large populations, not-predictable for individual molecules. The situation is exacerbated by the fact that biological systems are composed of cells and cells are, typically, small, and so contain relatively few molecules of each type (Milo and Phillips, 2015). There are typically one or two copies of each gene in a cell, and these may be different from one another (when heterozygous). The expression of any one gene depends upon the binding of specific proteins, transcription factors, that act to activate or repress gene expression. In contrast to a number of other cellular proteins, “as a rule of thumb, the concentrations of such transcription factors are in the nM range, corresponding to only 1-1000 copies per cell in bacteria or 103-106 in mammalian cells” (Milo and Phillips, 2015). Moreover, while DNA binding proteins bind to specific DNA sequences with high affinity, they also bind to DNA “non-specifically” in a largely sequence independent manner with low affinity. Given that there are many more non-specific (non-functional) binding sites in the DNA than functional ones, the effective concentration of a particular transcription factor can be significantly lower than its total cellular concentration would suggest. For example, in the case of the lac repressor of the bacterium Escherichia coli (discussed further below), there are estimated to be ~10 molecules of the tetrameric lac repressor per cell, but “non-specific affinity to the DNA causes >90% of LacI copies to be bound to the DNA at locations that are not the cognate promoter site” (Milo and Phillips, 2015); at most only a few molecules are free in the cytoplasm and available to bind to specific regulatory sites. Such low affinity binding to DNA allows proteins to undergo one-dimensional diffusion, a process that can greatly speed up the time it takes for a DNA binding protein to “find” high affinity binding sites (Stanford et al., 2000; von Hippel and Berg, 1989). Most transcription factors bind in a functionally significant manner to hundreds to thousands of gene regulatory sites per cell, often with distinct binding affinities. The effective binding affinity can also be influenced by positive and negative interactions with other transcription and accessory factors, chromatin structure, and DNA modifications. Functional complexes can take time to assemble, and once assembled can initiate multiple rounds of polymerase binding and activation, leading to a stochastic phenomena known as transcriptional bursting. An analogous process occurs with RNA-dependent polypeptide synthesis (translation). The result, particularly for genes expressed at lower levels, is that stochastic (unpredictable) bursts of transcription/translation can lead to functionally significant changes in protein levels (Raj et al., 2010; Raj and van Oudenaarden, 2008).

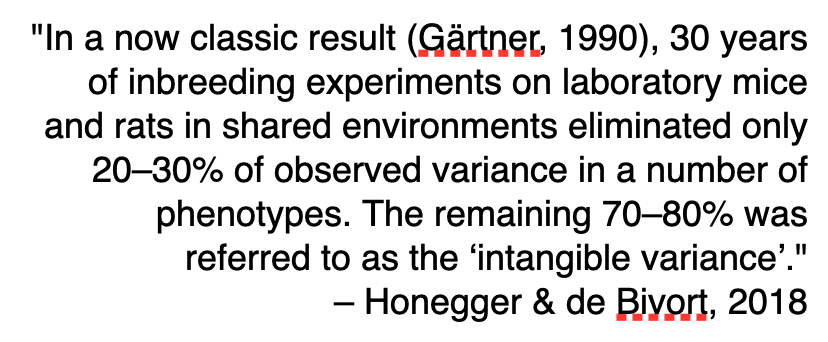

There are many examples of stochastic behaviors in biological systems. Originally noted by Novick and Weiner (1957) in their studies of the lac operon, it was clear that gene expression occurred in an all or none manner. This effect was revealed in a particularly compelling manner by Elowitz et al (2002) who used lac operon promoter elements to drive expression of transgenes encoding cyan and yellow fluorescent proteins (on a single plasmid) in E. coli. The observed behaviors were dramatic; genetically identical cells were found to express, stochastically, one, the other, both, or neither transgenes. The stochastic expression of genes and downstream effects appear to be the source of much of the variance found in organisms with the same genotype in the same environmental conditions (Honegger and de Bivort, 2018).

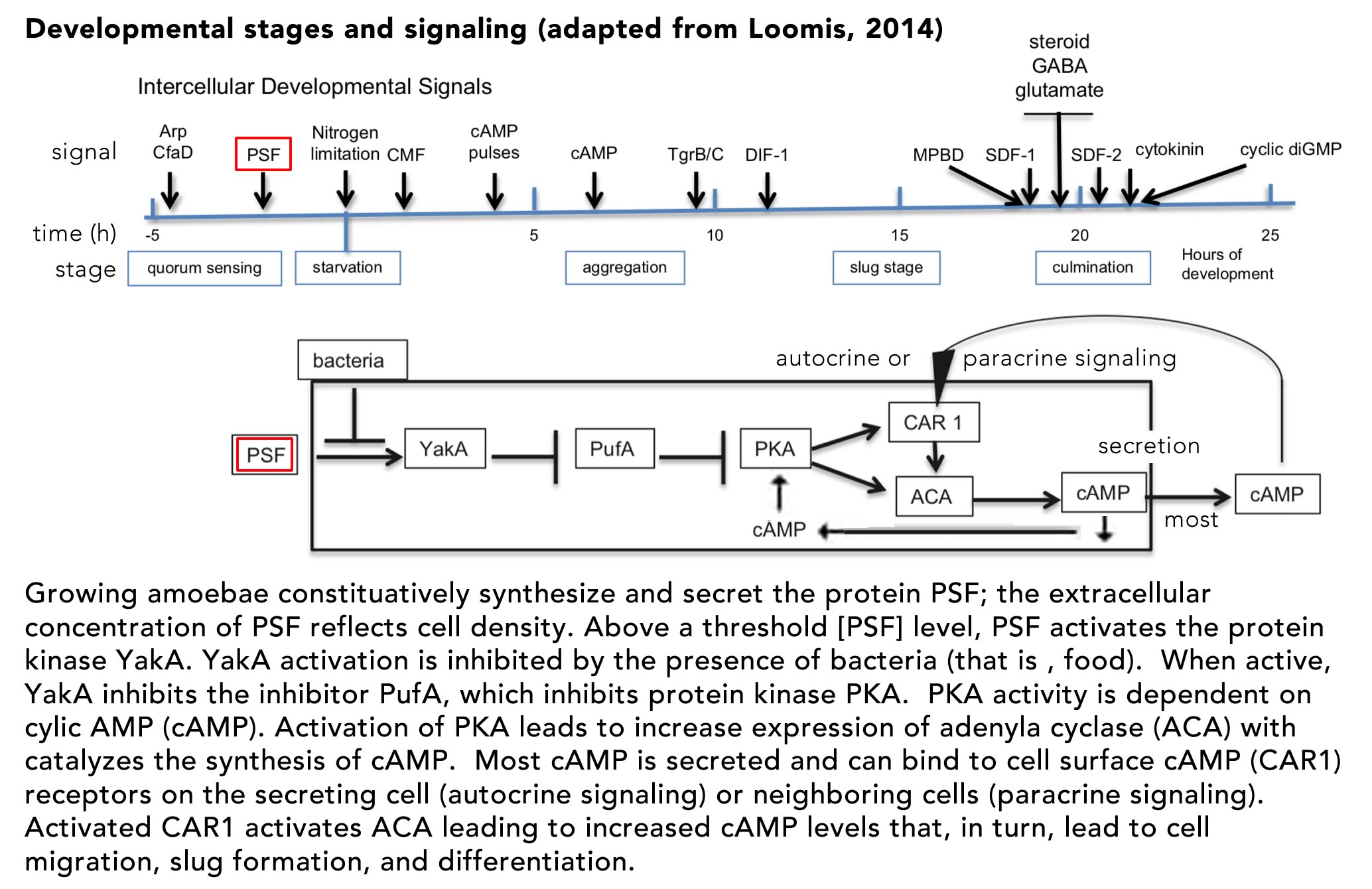

Beyond gene expression, the unpredictable effects of stochastic processes can be seen at all levels of biological organization, from the biased random walk behaviors that underlie various forms of chemotaxis (e.g. Spudich and Koshland, 1976) and the search behaviors in C. elegans (Roberts et al., 2016) and other animals (Smouse et al., 2010), the noisiness in the opening of individual neuronal voltage-gated ion channels (Braun, 2021; Neher and Sakmann, 1976), and various processes within the immune system (Hodgkin et al., 2014), to variations in the behavior of individual organisms (e.g. the leafhopper example cited by Honegger and de Bivort, 2018). Stochastic events are involved in a range of “social” processes in bacteria (Bassler and Losick, 2006). Their impact serves as a form of “bet-hedging” in populations that generate phenotypic variation in a homogeneous environment (see Symmons and Raj, 2016). Stochastic events can regulate the efficiency of replication-associated error-prone mutation repair (Uphoff et al., 2016) leading to increased variation in a population, particularly in response to environmental stresses. Stochastic “choices” made by cells can be seen as questions asked of the environment, the system’s response provides information that informs subsequent regulatory decisions (see Lyon, 2015) and the selective pressures on individuals in a population (Jablonka and Lamb, 2005). Together stochastic processes introduce a non-deterministic (i.e. unpredictable) element into higher order behaviors (Murakami et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2016).

Controlling stochasticity: While stochasticity can be useful, it also needs to be controlled. Not surprisingly then there are a number of strategies for “noise-suppression”, ranging from altering regulatory factor concentrations, the formation of covalent disulfide bonds between or within polypeptides, and regulating the activity of repair systems associated with DNA replication, polypeptide folding, and protein assembly via molecular chaperones and targeted degradation. For example, the identification of “cellular competition” effects has revealed that “eccentric cells” (sometimes, and perhaps unfortunately referred to as of “losers”) can be induced to undergo apoptosis (die) or migration in response to their “normal” neighbors (Akieda et al., 2019; Di Gregorio et al., 2016; Ellis et al., 2019; Hashimoto and Sasaki, 2020; Lima et al., 2021).

Student understanding of stochastic processes: There is ample evidence that students (and perhaps some instructors as well) are confused by or uncertain about the role of thermal motion, that is the transfer of kinetic energy via collisions, and the resulting stochastic behaviors in biological systems. As an example, Champagne-Queloz et al (2016; 2017) found that few students, even after instruction through molecular biology courses, recognize that collisions with other molecules were responsible for the disassembly of molecular complexes. In fact, many adopt a more “deterministic” model for molecular disassembly after instruction (see part A panel figure on next page). In earlier studies, we found evidence for a similar confusion among instructors (part B of figure on the next page)(Klymkowsky et al., 2010).

Introducing stochasticity to students: Given that understanding stochastic (random) processes can be difficult for many (e.g. Garvin-Doxas and Klymkowsky, 2008; Taleb, 2005), the question facing course designers and instructors is when and how best to help students develop an appreciation for the ubiquity, specific roles, and implications of stochasticity-dependent processes at all levels in biological systems. I would suggest that introducing students to the dynamics of non-covalent molecular interactions, prevalent in biological systems in the context of stochastic interactions (i.e. kinetic theory) rather than a ∆G-based approach may be useful. We can use the probability of garnering the energy needed to disrupt an interaction to present concepts of binding specificity (selectivity) and stability. Developing an understanding of the formation and disassembly of molecular interactions builds on the same logic that Albert Einstein and Ludwig Böltzman used to demonstrate the existence of atoms and molecules and the reversibility of molecular reactions (Bernstein, 2006). Moreover, as noted by Samoilov et al (2006) “stochastic mechanisms open novel classes of regulatory, signaling, and organizational choices that can serve as efficient and effective biological solutions to problems that are more complex, less robust, or otherwise suboptimal to deal with in the context of purely deterministic systems.”

The selectivity (specificity) and stability of molecular interactions can be understood from an energetic perspective – comparing the enthalpic and entropic differences between bound and unbound states. What is often missing from such discussions, aside from the fact of their inherent complexity, particularly in terms of calculating changes in entropy and exactly what is meant by energy (Cooper and Klymkowsky, 2013) is that many students enter biology classes without a robust understanding of enthalpy, entropy, or free energy (Carson and Watson, 2002). Presenting students with a molecular collision, kinetic theory-based mechanism for the dissociation of molecular interactions, may help them better understand (and apply) both the dynamics and specificity of molecular interactions. We can gage the strength of an interaction (the sum of the forces stabilizing an interaction) based on the amount of energy (derived from collisions with other molecules) needed to disrupt it. The implication of student responses to relevant Biology Concepts Instrument (BCI) questions and beSocratic activities (data not shown), as well as a number of studies in chemistry, is that few students consider the kinetic/vibrational energy delivered through collisions with other molecules (a function of temperature), as key to explaining why interactions break (see Carson and Watson, 2002 and references therein). Although this paper is 20 years old, there is little or no evidence that the situation has improved. Moreover, there is evidence that the conventional focus on mathematics-centered, free energy calculations in the absence of conceptual understanding may serve as an unnecessary barrier to the inclusion of a more socioeconomically diverse, and under-served populations of students (Ralph et al., 2022; Stowe and Cooper, 2019).

The lac operon as a context for introducing stochasticity: Studies of the E. coli lac operon hold an iconic place in the history of molecular biology and are often found in introductory courses, although typically presented in a deterministic context. The mutational analysis of the lac operon helped define key elements involved in gene regulation (Jacob and Monod, 1961; Monod et al., 1963). Booth et al (2022) used the lac operon as the context for their “modeling and simulation lesson”, Advanced Concepts in Regulation of the Lac Operon. Given its inherently stochastic regulation (Choi et al., 2008; Elowitz et al., 2002; Novick and Weiner, 1957; Vilar et al., 2003), the lac operon is a good place to start introducing students to stochastic processes. In this light, it is worth noting that Booth et al describes the behavior of the lac operon as “leaky”, which would seem to imply a low, but continuous level of expression, much as a leaky faucet continues to drip. As this is a peer-reviewed lesson, it seems likely that it reflects widely held mis-understandings of how stochastic processes are introduced to, and understood by students and instructors.

E. coli cells respond to the presence of lactose in growth media in a biphasic manner, termed diauxie, due to “the inhibitory action of certain sugars, such as glucose, on adaptive enzymes (meaning an enzyme that appears only in the presence of its substrate)” (Blaiseau and Holmes, 2021). When these (preferred) sugars are depleted from the media, growth slows. If lactose is present, however, growth will resume following a delay associated with the expression of the proteins encoded by the operon that enables the cell to import and metabolize lactose. Although the term homeostatic is used repeatedly by Booth et al, the lac operon is part of an adaptive, rather than a homeostatic, system. In the absence of glucose, cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels in the cell rise. cAMP binds to and activates the catabolite activator protein (CAP), encoded for by the crp gene. Activation of CAP leads to the altered expression of a number of target genes, whose products are involved in adaption to the stress associated with the absence of common and preferred metabolites. cAMP-activated CAP acts as both a transcriptional repressor and activator, “and has been shown to regulate hundreds of genes in the E. coli genome, earning it the status of “global” or “master” regulator” (Frendorf et al., 2019). It is involved in the adaptation to environmental factors, rather than maintaining the cell in a particular state (homeostasis).

The lac operon is a classic polycistronic bacterial gene, encoding three distinct polypeptides: lacZ (β-galactosidase), lacY (β-galactoside permease), and lacA (galactoside acetyltransferase). When glucose or other preferred energy sources are present, expression of the lac operon is blocked by the inactivity of CAP. The CAP protein is a homodimer and its binding to DNA is regulated by the binding of the allosteric effector cAMP. cAMP is generated from ATP by the enzyme adenylate cyclase, encoded by the cya gene. In the absence of glucose the enyzme encoded by the crr gene is phosphorylated and acts to activate adenylate cyclase (Krin et al., 2002). As cAMP levels increase, cAMP binds to the CAP protein, leading to a dramatic change in its structure (↑), such that the protein’s DNA binding domain becomes available to interact with promoter sequences (figure from Sharma et al., 2009).

Binding of activated (cAMP-bound) CAP is not, by itself sufficient to activate expression of the lac operon because of the presence of the constitutively expressed lac repressor protein, encoded for by the lacI gene. The active repressor is a tetramer, present at very low levels (~10 molecules) per cell. The lac operon contains three repressor (“operator”) binding sites; the tetrameric repressor can bind two operator sites simultaneously (upper figure → from Palanthandalam-Madapusi and Goyal, 2011). In the absence of lactose, but in the presence of cAMP-activated CAP, the operon is expressed in discrete “bursts” (Novick and Weiner, 1957; Vilar et al., 2003). Choi et al (2008) found that these burst come in two types, short and long, with the size of the burst referring to the number of mRNA molecules synthesized (bottm figure adapted from Choi et al ↑). The difference between burst sizes arises from the length of time that the operon’s repressor binding sites are unoccupied by repressor. As noted above, the tetravalent repressor protein can bind to two operator sites at the same time. When released from one site, polymerase binding and initiation produces a small number of mRNA molecules. Persistent binding to the second site means that the repressor concentration remains locally high, favoring rapid rebinding to the operator and the cessation of transcription (RNA synthesis). When the repressor releases from both operator sites, a rarer event, it is free to diffuse away and interact (non-specifically, i.e. with low affinity) with other DNA sites in the cell, leaving the lac operator sites unoccupied for a longer period of time. The number of such non-specific binding sites greatly exceeds the number (three) of specific binding sites in the operon. The result is the synthesis of a larger “burst” (number) of mRNA molecules. The average length of time that the operator sites remain unoccupied is a function of the small number of repressor molecules present and the repressor’s low but measurable non-sequence specific binding to DNA.

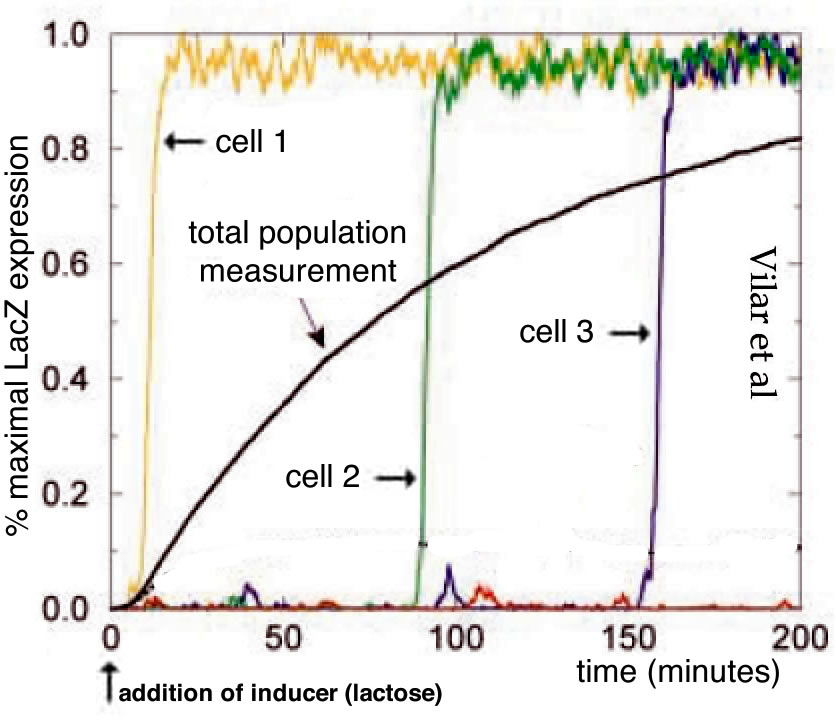

The expression of the lac operon leads to the appearance of β-galactosidase and β-galactoside permease. An integral membrane protein, β-galactoside permease enables extracellular lactose to enter the cell while cytoplasmic β-galactosidase catalyzes its breakdown and the generation of allolactone, which binds to the lac repressor protein, inhibiting its binding to operator sites, and so removing repression of transcription. In the absence of lactose, there are few if any of the proteins (β-galactosidase and β-galactoside permease) needed to activate the expression of the lac operon, so the obvious question is how, when lactose does appear in the extracellular media, does the lac operon turn on? Booth et al and the Wikipedia entry on the lac operon (accessed 29 June 2022) describe the turn on of the lac operon as “leaky” (see above). The molecular modeling studies of Vilar et al and Choi et al (which, together with Novick and Weiner, are not cited by Booth et al) indicate that the system displays distinct threshold and maintenance concentrations of lactose needed for stable lac gene expression. The term “threshold” does not occur in the Booth et al article. More importantly, when cultures are examined at the single cell level, what is observed is not a uniform increase in lac expression in all cells, as might be expected in the context of leaky expression, but more sporadic (noisy) behaviors. Increasing numbers of cells are “full on” in terms of lac operon expression over time when cultured in lactose concentrations above the operon’s activation threshold. This illustrates the distinctly different implications of a leaky versus a stochastic process in terms of their impacts on gene expression. While a leak is a macroscopic metaphor that produces a continuous, dependable, regular flow (drips), the occurrence of “bursts” of gene expression implies a stochastic (unpredictable) process ( figure from Vilar et al ↓).

As the ubiquity and functionally significant roles of stochastic processes in biological systems becomes increasingly apparent, e.g. in the prediction of phenotypes from genotypes (Karavani et al., 2019; Mostafavi et al., 2020), helping students appreciate and understand the un-predictable, that is stochastic, aspects of biological systems becomes increasingly important. As an example, revealed dramatically through the application of single cell RNA sequencing studies, variations in gene expression between cells of the same “type” impacts organismic development and a range of behaviors. For example, in diploid eukaryotic cells is now apparent that in many cells, and for many genes, only one of the two alleles present is expressed; such “monoallelic” expression can impact a range of processes (Gendrel et al., 2014). Given that stochastic processes are often not well conveyed through conventional chemistry courses (Williams et al., 2015) or effectively integrated into, and built upon in molecular (and other) biology curricula; presenting them explicitly in introductory biology courses seems necessary and appropriate.

It may also help make sense of discussions of whether humans (and other organisms) have “free will”. Clearly the situation is complex. From a scientific perspective we are analyzing systems without recourse to non-natural processes. At the same time, “Humans typically experience freely selecting between alternative courses of action” (Maoz et al., 2019)(Maoz et al., 2019a; see also Maoz et al., 2019b). It seems possible that recognizing the intrinsically unpredictable nature of many biological processes (including those of the central nervous system) may lead us to conclude that whether or not free will exists is in fact a non-scientific, unanswerable (and perhaps largely meaningless) question.

footnotes

[1] For this discussion I will ignore entropy, a factor that figures in whether a particular reaction in favorable or unfavorable, that is whether, and the extent to which it occurs.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Melanie Cooper and Nick Galati for taking a look and Chhavinder Singh for getting it started. Updated 6 January 2023.

literature cited:

Akieda, Y., Ogamino, S., Furuie, H., Ishitani, S., Akiyoshi, R., Nogami, J., Masuda, T., Shimizu, N., Ohkawa, Y. and Ishitani, T. (2019). Cell competition corrects noisy Wnt morphogen gradients to achieve robust patterning in the zebrafish embryo. Nature communications 10, 1-17.

Alberts, B. (1998). The cell as a collection of protein machines: preparing the next generation of molecular biologists. Cell 92, 291-294.

Bassler, B. L. and Losick, R. (2006). Bacterially speaking. Cell 125, 237-246.

Bernstein, J. (2006). Einstein and the existence of atoms. American journal of physics 74, 863-872.

Blaiseau, P. L. and Holmes, A. M. (2021). Diauxic inhibition: Jacques Monod’s Ignored Work. Journal of the History of Biology 54, 175-196.

Booth, C. S., Crowther, A., Helikar, R., Luong, T., Howell, M. E., Couch, B. A., Roston, R. L., van Dijk, K. and Helikar, T. (2022). Teaching Advanced Concepts in Regulation of the Lac Operon With Modeling and Simulation. CourseSource.

Braun, H. A. (2021). Stochasticity Versus Determinacy in Neurobiology: From Ion Channels to the Question of the “Free Will”. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 15, 39.

Carson, E. M. and Watson, J. R. (2002). Undergraduate students’ understandings of entropy and Gibbs free energy. University Chemistry Education 6, 4-12.

Champagne-Queloz, A. (2016). Biological thinking: insights into the misconceptions in biology maintained by Gymnasium students and undergraduates”. In Institute of Molecular Systems Biology. Zurich, Switzerland: ETH Zürich.

Champagne-Queloz, A., Klymkowsky, M. W., Stern, E., Hafen, E. and Köhler, K. (2017). Diagnostic of students’ misconceptions using the Biological Concepts Instrument (BCI): A method for conducting an educational needs assessment. PloS one 12, e0176906.

Choi, P. J., Cai, L., Frieda, K. and Xie, X. S. (2008). A stochastic single-molecule event triggers phenotype switching of a bacterial cell. Science 322, 442-446.

Coop, G. and Przeworski, M. (2022). Lottery, luck, or legacy. A review of “The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA matters for social equality”. Evolution 76, 846-853.

Cooper, M. M. and Klymkowsky, M. W. (2013). The trouble with chemical energy: why understanding bond energies requires an interdisciplinary systems approach. CBE Life Sci Educ 12, 306-312.

Di Gregorio, A., Bowling, S. and Rodriguez, T. A. (2016). Cell competition and its role in the regulation of cell fitness from development to cancer. Developmental cell 38, 621-634.

Ellis, S. J., Gomez, N. C., Levorse, J., Mertz, A. F., Ge, Y. and Fuchs, E. (2019). Distinct modes of cell competition shape mammalian tissue morphogenesis. Nature 569, 497.

Elowitz, M. B., Levine, A. J., Siggia, E. D. and Swain, P. S. (2002). Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science 297, 1183-1186.

Feldman, M. W. and Riskin, J. (2022). Why Biology is not Destiny. In New York Review of Books. NY.

Frendorf, P. O., Lauritsen, I., Sekowska, A., Danchin, A. and Nørholm, M. H. (2019). Mutations in the global transcription factor CRP/CAP: insights from experimental evolution and deep sequencing. Computational and structural biotechnology journal 17, 730-736.

Garvin-Doxas, K. and Klymkowsky, M. W. (2008). Understanding Randomness and its impact on Student Learning: Lessons from the Biology Concept Inventory (BCI). Life Science Education 7, 227-233.

Gendrel, A.-V., Attia, M., Chen, C.-J., Diabangouaya, P., Servant, N., Barillot, E. and Heard, E. (2014). Developmental dynamics and disease potential of random monoallelic gene expression. Developmental cell 28, 366-380.

Harden, K. P. (2021). The genetic lottery: why DNA matters for social equality: Princeton University Press.

Hashimoto, M. and Sasaki, H. (2020). Cell competition controls differentiation in mouse embryos and stem cells. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 67, 1-8.

Hodgkin, P. D., Dowling, M. R. and Duffy, K. R. (2014). Why the immune system takes its chances with randomness. Nature Reviews Immunology 14, 711-711.

Honegger, K. and de Bivort, B. (2018). Stochasticity, individuality and behavior. Current Biology 28, R8-R12.

Hull, M. M. and Hopf, M. (2020). Student understanding of emergent aspects of radioactivity. International Journal of Physics & Chemistry Education 12, 19-33.

Jablonka, E. and Lamb, M. J. (2005). Evolution in four dimensions: genetic, epigenetic, behavioral, and symbolic variation in the history of life. Cambridge: MIT press.

Jacob, F. and Monod, J. (1961). Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. Journal of molecular biology 3, 318-356.

Karavani, E., Zuk, O., Zeevi, D., Barzilai, N., Stefanis, N. C., Hatzimanolis, A., Smyrnis, N., Avramopoulos, D., Kruglyak, L. and Atzmon, G. (2019). Screening human embryos for polygenic traits has limited utility. Cell 179, 1424-1435. e1428.

Klymkowsky, M. W., Kohler, K. and Cooper, M. M. (2016). Diagnostic assessments of student thinking about stochastic processes. In bioArXiv: http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2016/05/20/053991.

Klymkowsky, M. W., Underwood, S. M. and Garvin-Doxas, K. (2010). Biological Concepts Instrument (BCI): A diagnostic tool for revealing student thinking. In arXiv: Cornell University Library.

Krin, E., Sismeiro, O., Danchin, A. and Bertin, P. N. (2002). The regulation of Enzyme IIAGlc expression controls adenylate cyclase activity in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 148, 1553-1559.

Lima, A., Lubatti, G., Burgstaller, J., Hu, D., Green, A., Di Gregorio, A., Zawadzki, T., Pernaute, B., Mahammadov, E. and Montero, S. P. (2021). Cell competition acts as a purifying selection to eliminate cells with mitochondrial defects during early mouse development. bioRxiv, 2020.2001. 2015.900613.

Lyon, P. (2015). The cognitive cell: bacterial behavior reconsidered. Frontiers in microbiology 6, 264.

Maoz, U., Sita, K. R., Van Boxtel, J. J. and Mudrik, L. (2019a). Does it matter whether you or your brain did it? An empirical investigation of the influence of the double subject fallacy on moral responsibility judgments. Frontiers in Psychology 10, 950.

Maoz, U., Yaffe, G., Koch, C. and Mudrik, L. (2019b). Neural precursors of decisions that matter—an ERP study of deliberate and arbitrary choice. Elife 8, e39787.

Milo, R. and Phillips, R. (2015). Cell biology by the numbers: Garland Science.

Monod, J., Changeux, J.-P. and Jacob, F. (1963). Allosteric proteins and cellular control systems. Journal of molecular biology 6, 306-329.

Mostafavi, H., Harpak, A., Agarwal, I., Conley, D., Pritchard, J. K. and Przeworski, M. (2020). Variable prediction accuracy of polygenic scores within an ancestry group. Elife 9, e48376.

Murakami, M., Shteingart, H., Loewenstein, Y. and Mainen, Z. F. (2017). Distinct sources of deterministic and stochastic components of action timing decisions in rodent frontal cortex. Neuron 94, 908-919. e907.

Neher, E. and Sakmann, B. (1976). Single-channel currents recorded from membrane of denervated frog muscle fibres. Nature 260, 799-802.

Novick, A. and Weiner, M. (1957). Enzyme induction as an all-or-none phenomenon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 43, 553-566.

Palanthandalam-Madapusi, H. J. and Goyal, S. (2011). Robust estimation of nonlinear constitutive law from static equilibrium data for modeling the mechanics of DNA. Automatica 47, 1175-1182.

Raj, A., Rifkin, S. A., Andersen, E. and van Oudenaarden, A. (2010). Variability in gene expression underlies incomplete penetrance. Nature 463, 913-918.

Raj, A. and van Oudenaarden, A. (2008). Nature, nurture, or chance: stochastic gene expression and its consequences. Cell 135, 216-226.

Ralph, V., Scharlott, L. J., Schafer, A., Deshaye, M. Y., Becker, N. M. and Stowe, R. L. (2022). Advancing Equity in STEM: The Impact Assessment Design Has on Who Succeeds in Undergraduate Introductory Chemistry. JACS Au.

Roberts, W. M., Augustine, S. B., Lawton, K. J., Lindsay, T. H., Thiele, T. R., Izquierdo, E. J., Faumont, S., Lindsay, R. A., Britton, M. C. and Pokala, N. (2016). A stochastic neuronal model predicts random search behaviors at multiple spatial scales in C. elegans. Elife 5, e12572.

Samoilov, M. S., Price, G. and Arkin, A. P. (2006). From fluctuations to phenotypes: the physiology of noise. Science’s STKE 2006, re17-re17.

Sharma, H., Yu, S., Kong, J., Wang, J. and Steitz, T. A. (2009). Structure of apo-CAP reveals that large conformational changes are necessary for DNA binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, 16604-16609.

Smouse, P. E., Focardi, S., Moorcroft, P. R., Kie, J. G., Forester, J. D. and Morales, J. M. (2010). Stochastic modelling of animal movement. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 365, 2201-2211.

Spudich, J. L. and Koshland, D. E., Jr. (1976). Non-genetic individuality: chance in the single cell. Nature 262, 467-471.

Stanford, N. P., Szczelkun, M. D., Marko, J. F. and Halford, S. E. (2000). One-and three-dimensional pathways for proteins to reach specific DNA sites. The EMBO Journal 19, 6546-6557.

Stowe, R. L. and Cooper, M. M. (2019). Assessment in Chemistry Education. Israel Journal of Chemistry.

Symmons, O. and Raj, A. (2016). What’s Luck Got to Do with It: Single Cells, Multiple Fates, and Biological Nondeterminism. Molecular cell 62, 788-802.

Taleb, N. N. (2005). Fooled by Randomness: The hidden role of chance in life and in the markets. (2nd edn). New York: Random House.

Uphoff, S., Lord, N. D., Okumus, B., Potvin-Trottier, L., Sherratt, D. J. and Paulsson, J. (2016). Stochastic activation of a DNA damage response causes cell-to-cell mutation rate variation. Science 351, 1094-1097.

You, Shu-Ting, and Jun-Yi Leu. “Making sense of noise.” Evolutionary Biology—A Transdisciplinary Approach(2020): 379-391.

Vilar, J. M., Guet, C. C. and Leibler, S. (2003). Modeling network dynamics: the lac operon, a case study. J Cell Biol 161, 471-476.

von Hippel, P. H. and Berg, O. G. (1989). Facilitated target location in biological systems. Journal of Biological Chemistry 264, 675-678.

Williams, L. C., Underwood, S. M., Klymkowsky, M. W. and Cooper, M. M. (2015). Are Noncovalent Interactions an Achilles Heel in Chemistry Education? A Comparison of Instructional Approaches. Journal of Chemical Education 92, 1979–1987.