A RAG-ChatGPT written backgrounder (checked and edited by Mike Klymkowsky ) for the excessively curious – in support of biofundamentals – 1 August 2025

Weldon’s Background and Perspective: Walter F. R. Weldon (1860–1906) was a British zoologist and a pioneer of biometry – the statistical study of biological variation. He believed that evolution operated through numerous small, continuous variations rather than abrupt, either-or traits. In his studies of creatures like shrimps and crabs, Weldon found that even traits which appeared dimorphic at first could grade into one another when large enough samples were measured [link]. He and his colleague Karl Pearson (1857-1936) argued that Darwin’s theory of natural selection was best tested with quantitative methods: “the questions raised by the Darwinian hypothesis are purely statistical, and the statistical method is the only one at present obvious by which that hypothesis can be experimentally checked” [link]. This emphasis on gradual variation and statistical analysis set Weldon at odds with the emerging Mendelian school of genetics, led by William Bateson (1861-1926) that focused on discrete traits and sudden changes. By 1902, the scientific community had split into two camps – the biometricians (Weldon and Pearson in London) versus the Mendelians (Bateson and allies in Cambridge) – reflecting deep disagreements over the nature of heredity [link]. This was the charged backdrop against which Weldon evaluated Gregor Mendel’s pea-breeding experiments.

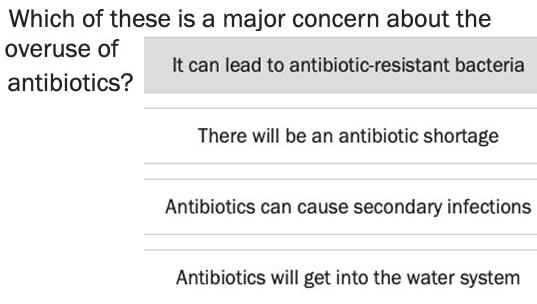

Critique of Mendel’s Pea Traits and Categories Weldon’s photographic plate of peas illustrating continuous variation in seed color. (This figure from his 1902 paper shows pea seeds ranging from green to yellow in a smooth gradient, contradicting the clear-cut “green vs. yellow” categories assumed by Mendel [link]. Images 1–6 and 7–12 (top rows) display the range of cotyledon colors in two different pea varieties after the seed coats were removed [link]. Instead of all seeds being simply green or yellow, Weldon documented many intermediate shades. He even found seeds whose two cotyledons (halves) differed in color, underscoring that Mendel’s binary categories were oversimplifications of a more complex reality [link].

Weldon closely re-examined the seven pea traits Mendel had chosen (such as seed color and seed shape) and argued that Mendel’s tidy classifications did not reflect biological reality in peas. In Mendel’s account, peas were either “green” or “yellow” and produced either “round, smooth” or “wrinkled” seeds, with nothing in between. Weldon showed this was an artifact of Mendel’s experimental design. He gathered peas from diverse sources and found continuous variation rather than strict binary types. For example, a supposedly pure “round-seeded” variety produced seeds with varying degrees of roundness and wrinkling [link]. Likewise, seeds that would be classified as “green” or “yellow” in Mendel’s scheme actually exhibited a spectrum of color tones from deep green through greenish-yellow to bright yellow [link]. Weldon’s observations were impossible to reconcile with a simple either/or trait definition [link].

Weldon concluded that Mendel had deliberately picked atypical pea strains with stark, discontinuous traits, and that Mendel’s category labels (e.g. “green vs. yellow” seeds) obscured the true, much more variable nature of those characters [link]. In Weldon’s view, the neat ratios Mendel obtained were only achievable because Mendel worked with artificially generated lines of peas, bred to eliminate intermediate forms [link]. In ordinary pea populations that a farmer or naturalist might encounter, such clear-cut divisions virtually disappeared: “Many races of peas are exceedingly variable, both in colour and in shape,” Weldon noted, “so that both the category ‘round and smooth’ and the category ‘wrinkled and irregular’ include a considerable range of varieties.” [link] In short, he felt Mendel’s chosen traits were too simple and unrepresentative. The crisp binary traits in Mendel’s experiments were the exception, not the rule, in nature. Weldon’s extensive survey of pea varieties led him to believe that Mendel’s results “had no validity beyond the artificially “purified”in-bred” races Mendel worked with,” because the binary categories “obscured a far more variable reality.”[link]

Mendel’s Conclusions and Real-World Heredity. Weldon went beyond critiquing Mendel’s choice of traits – he questioned whether Mendel’s conclusions about heredity were biologically meaningful for understanding inheritance in real populations. Based on his empirical findings and evolutionary perspective, Weldon doubted that Mendel’s laws could serve as general laws of heredity. Some of his major biological objections were:

– Traits are seldom purely binary in nature: Outside the monk’s garden, most characteristics do not sort into a few discrete classes. Instead, they form continuous gradations. Weldon realized that Mendel’s insistence on traits segregating neatly into “either/or” categories “simply wasn’t true,” even for peas [link]. Mendel’s clear ratios were achieved by excluding the normal range of variation; in the wild, peas varied continuously from yellow to green with every shade in between [link]. What Mendel presented as unitary “characters” were, in Weldon’s eyes, extremes picked from a continuum.

– Mendel’s results were an artifact of pure-breeding: Weldon argued that the famous 3:1 ratios and other patterns were only apparent because Mendel had used highly inbred, “pure” varieties. By extensive inbreeding and selection, Mendel stripped away intermediate variants [link]. The artificially uniform parent strains used in Mendel’s experiments do not reflect natural populations. Weldon concluded that the seeming universality of Mendel’s laws was misleading – they described those special pea strains, not peas (or other organisms) at large [link]. In a letter, he even mused whether Mendel’s remarkably clean data were “too good” to be true, hinting that real-world data would rarely align so perfectly [link].

– Dominance is not an absolute property: A cornerstone of Mendelism was that one trait form is dominant over the other (e.g. yellow dominates green). Weldon questioned this simplistic view. He gathered evidence that whether a given trait appears dominant or recessive can depend on context – on the plant’s overall genetic background and environmental conditions [link]. For example, a seed color might behave as dominant in one cross but not in another, if other genetic factors differ. Weldon argued that Mendel’s concept of dominance was “oversimplified” because it treated dominance as inherent to a trait, independent of development or ancestry [link]. In reality (as Weldon emphasized), “the effect of the same bit of chromosome can be different depending on the hereditary background and the wider environmental conditions”, so an inherited character’s expression isn’t fixed as purely dominant or recessive [link]. This questioned the biological generality of Mendel’s one-size-fits-all dominance rule.

– Atavism and ancestral influence: Perhaps most intriguing was Weldon’s concern with reversion (atavism) – cases where an offspring exhibits a trait of a distant ancestor that had seemingly disappeared in intervening generations. Breeders of plants and animals had long reported that occasionally a “throwback” individual would appear, showing an old parental form or color after many generations of absence. To Weldon, such phenomena implied that heredity isn’t solely about the immediate parents’ genes, but can be influenced by more remote ancestral contributions [link]. “Mendel treats such characters as if the condition in two given parents determined the condition in all their offspring,” Weldon wrote, but breeders know that “the condition of an organism does not as a rule depend upon [any one pair of ancestors] alone, but in varying degrees upon the condition of all its ancestors in every past generation” [link]. In other words, the influence of a trait could accumulate or skip generations. This idea directly conflicted with Mendel’s theory as presented in 1900, which only considered inheritance from the two parents and had no mechanism for latent ancestral traits resurfacing after several generations. Weldon concluded from examples of reversion that Mendel’s framework was biologically incomplete – there had to be “more going on” in heredity than Mendel’s laws acknowledged [link].

In sum, Weldon found Mendel’s laws too limited and idealized to account for the messy realities of inheritance in natural populations. Mendel had demonstrated elegant numerical ratios with a few pea characters, but Weldon did not believe those results scaled up to the complex heredity of most traits or species. Variation, continuity, and context were central in Weldon’s view of biology, whereas Mendel’s work (as interpreted by Mendel’s supporters) seemed to ignore those factors. Thus, Weldon saw Mendel’s conclusions as at best a special case – interesting, but not the whole story of heredity in the real world [link][link].

Weldon’s Legacy

Weldon’s critiques came at a time of intense debate between the “Mendelians” and the “Biometricians.” William Bateson, the chief Mendelian, vehemently defended Mendel’s theory against Weldon’s attacks. In 1902, Bateson published a lengthy rebuttal titled Mendel’s Principles of Heredity: A Defense, including a 100-page polemic aimed squarely at “defending Mendel from Professor Weldon”[link]. Bateson and his allies believed Weldon had misinterpreted Mendel and that discrete Mendelian factors really were the key to heredity. The clash between Weldon and Bateson grew increasingly personal and public. By 1904 the feud had become so heated that the editor of Nature refused to publish any further exchanges between the two sides [link]. At a 1904 British Association meeting, a debate between Bateson and Weldon on evolution and heredity became a shouting match, emblematic of how divisive the issue had become [link][link].

Although Weldon’s objections were rooted in biological observations, many contemporaries saw the dispute as one of old guard vs. new ideas. Tragically, Weldon died in 1906 at the age of 46, with a major manuscript on inheritance still unfinished [link]. In that unpublished work, he had gathered experimental data to support a more nuanced theory reconciling heredity with development and ancestral effects [link][link]. With his early death, much of Weldon’s larger critique faded from the spotlight. Mendelian genetics, championed by Bateson and later enriched by the chromosome theory, surged ahead. Nevertheless, in hindsight many of Weldon’s points were remarkably prescient. His insistence on looking at population-level variation and the importance of multiple factors and environment foreshadowed the modern understanding that Mendelian genes can interact in complex ways (for example, polygenic inheritance and gene-by-environment effects). As one historian noted, Weldon’s critiques of Mendelian principles were “100 years ahead of his time” [link]. In the context of his era, Weldon doubted the biological relevance of Mendel’s peas for the broader canvas of life – and while Mendel’s laws did prove fundamental, Weldon was correct that real-world heredity is more intricate than simple pea traits. His challenge to Mendelism ultimately pushed geneticists to grapple with continuous variation and population dynamics, helping lay the groundwork for the synthesis of Mendelian genetics with biometry in the decades after his death[link][link].

Sources: Weldon’s 1902 paper in Biometrika and historical analyses [link][link][link][link][link][link][link]provide the basis for the above summary. These document Weldon’s arguments that Mendel’s pea traits were overly simplistic and his laws of heredity not universally applicable to natural populations, especially in light of continuous variation, context-dependent trait expression, and atavistic reversions. The debate between Weldon and the Mendelians is detailed in contemporary accounts and later historical reviews [link][link], illustrating the scientific and conceptual rift that formed around Mendel’s rediscovered work.