The Dunning-Kruger (DK) effect is the well-established phenomenon that people tend to over estimate their understanding of a particular topic or their skill at a particular task, often to a dramatic degree [link][link]. We see examples of the DK effect throughout society; the current administration (unfortunately) and the nutritional supplements / homeopathy section of Whole Foods spring to mind as examples. But there is a less well-recognized “reverse DK” effect, namely the tendency of instructors, and a range of other public communicators, to over-estimate what the people they are talking to are prepared to understand, appreciate, and accurately apply. The efforts of science communicators and instructors can be entertaining but the failure to recognize and address the reverse DK effect results in ineffective educational efforts. These efforts can themselves help generate the illusion of understanding in students and the broader public (discussed here). While a confused understanding of the intricacies of cosmology or particle physics can be relatively harmless in their social and personal implications, similar misunderstandings become personally and publicly significant when topics such as vaccination, alternative medical treatments, and climate change are in play.

There are two synergistic aspects to the reverse DK effect that directly impact science instruction: the need to understand what one’s audience does not understand together with the need to clearly articulate the conceptual underpinnings needed to understand the subject to be taught. This is in part because modern science has, at its core, become increasingly counter-intuitive over the last approximately 100 years or so, a situation that can cause serious confusions that educators must address directly and explicitly. The first reverse DK effect involves the extent to which the instructor (and by implication the course and textbook designer) has an accurate appreciation of what students think or think they know, what ideas they have previously been exposed to, and what they actually understand about the implications of those ideas. Are they prepared to learn a subject or does the instructor first have to acknowledge and address conceptual confusions and build or rebuild base concepts? While the best way to discover what students think is arguably a Socratic discussion, this only rarely occurs for a range of practical reasons. In its place, a number of concept inventory-type testing instruments have been generated to reveal whether various pre-identified common confusions exist in students’ thinking. Knowing the results of such assessments BEFORE instruction can help customize how the instructor structures the learning environment and content to be presented and whether the instructor gives students the space to work with these ideas to develop a more accurate and nuanced understanding of a topic. Of course, this implies that instructors have the flexibility to adjust the pace and focus of their classroom activities. Do they take the time needed to address student issues or do they feel pressured to plow through the prescribed course content, come hell, high water, or cascading student befuddlement.

A complementary aspect of the reverse DK effect, well-illustrated in the “why magnets attract” interview with the physicist Richard Feynman, is that the instructor, course designer, or textbook author(s) needs to have a deep and accurate appreciation of the underlying core knowledge necessary to understand the topic they are teaching. Such a robust conceptual understanding makes it possible to convey the complexities involved in a particular process and explicitly values appreciating a topic rather than memorizing it. It focuses on the general, rather than the idiosyncratic. A classic example from many an introductory biology course is the difference between expecting students to remember the steps in glycolysis or the Krebs cycle reaction system, as opposed to the general principles that underlie the non-equilibrium reaction networks involved in all biological functions, a reaction network based on coupled chemical reactions and governed by the behaviors of thermodynamically favorable and unfavorable reactions. Without a explicit discussion of these topics, all too often students are required to memorize names without understanding the underlying rationale driving the processes involved; that is, why the system behaves as it does. Instructors also give false “rubber band” analogies or heuristics to explain complex phenomena (see Feynman video 6:18 minutes in). A similar situation occurs when considering how molecules come to associate and dissociate from one another, for example in the process of regulating gene expression or repairing mutations in DNA. Most textbooks simply do not discuss the physiochemical processes involved in binding specificity, association, and dissociation rates, such as the energy changes associated with molecular interactions and thermal collisions (don’t believe me? look for yourself!). But these factors are essential for a student to understand the dynamics of gene expression [link], as well as the specificity of modern methods involved in genetic engineering, such as restriction enzymes, polymerase chain reaction, and CRISPR CAS9-mediated mutagenesis. By focusing on the underlying processes involved we can avoid their trivialization and enable students to apply basic principles to a broad range of situations. We can understand exactly why CRISPR CAS9-directed mutagenesis can be targeted to a single site within a multibillion-base pair genome.

Of course, as in the case of recognizing and responding to student misunderstandings and knowledge gaps, a thoughtful consideration of underlying processes takes course time, time that trades the development of a working understanding of core processes and principles for broader “coverage” of frequently disconnected facts, the memorization and regurgitation of which has been privileged over understanding why those facts are worth knowing. If our goal is for students to emerge from a course with an accurate understanding of the basic processes involved rather than a superficial familiarity with a plethora of unrelated facts, however, a Socratic interaction with the topic is essential. What assumptions are being made, where do they come from, how do they constrain the system, and what are their implications? Do we understand why the system behaves the way it does? In this light, it is a serious educational mystery that many molecular biology / biochemistry curricula fail to introduce students to the range of selective and non-selective evolutionary mechanisms (including social and sexual selection – see link), that is, the processes that have shaped modern organisms.

Both aspects of the reverse DK effect impact educational outcomes. Overcoming the reverse DK effect depends on educational institutions committing to effective and engaging course design, measured in terms of retention, time to degree, and a robust inquiry into actual student learning. Such an institutional dedication to effective course design and delivery is necessary to empower instructors and course designers. These individuals bring a deep understanding of the topics taught and their conceptual foundations and historic development to their students AND must have the flexibility and authority to alter the pace (and design) of a course or a curriculum when they discover that their students lack the pre-existing expertise necessary for learning or that the course materials (textbooks) do not present or emphasize necessary ideas.  Unfortunately, all too often instructors, particularly in introductory level college science courses, are not the masters of their ships; that is, they are not rewarded for generating more effective course materials. An emphasis on course “coverage” over learning, whether through peer-pressure, institutional apathy, or both, generates unnecessary obstacles to both student engagement and content mastery. To reverse the effects of the reverse DK effect, we need to encourage instructors, course designers, and departments to see the presentation of core disciplinary observations and concepts as the intellectually challenging and valuable endeavor that it is. In its absence, there are serious (and growing) pressures to trivialize or obscure the educational experience – leading to the socially- and personally-damaging growth of fake knowledge.

Unfortunately, all too often instructors, particularly in introductory level college science courses, are not the masters of their ships; that is, they are not rewarded for generating more effective course materials. An emphasis on course “coverage” over learning, whether through peer-pressure, institutional apathy, or both, generates unnecessary obstacles to both student engagement and content mastery. To reverse the effects of the reverse DK effect, we need to encourage instructors, course designers, and departments to see the presentation of core disciplinary observations and concepts as the intellectually challenging and valuable endeavor that it is. In its absence, there are serious (and growing) pressures to trivialize or obscure the educational experience – leading to the socially- and personally-damaging growth of fake knowledge.

empty images holders removed, new image added – 17 December 2020

The Nobel prize winning work of Kazutoshi Takahashi and Shinya Yamanaka (

The Nobel prize winning work of Kazutoshi Takahashi and Shinya Yamanaka ( system. The left panel of the figure shows, in highly schematic form how these cells interact (

system. The left panel of the figure shows, in highly schematic form how these cells interact (

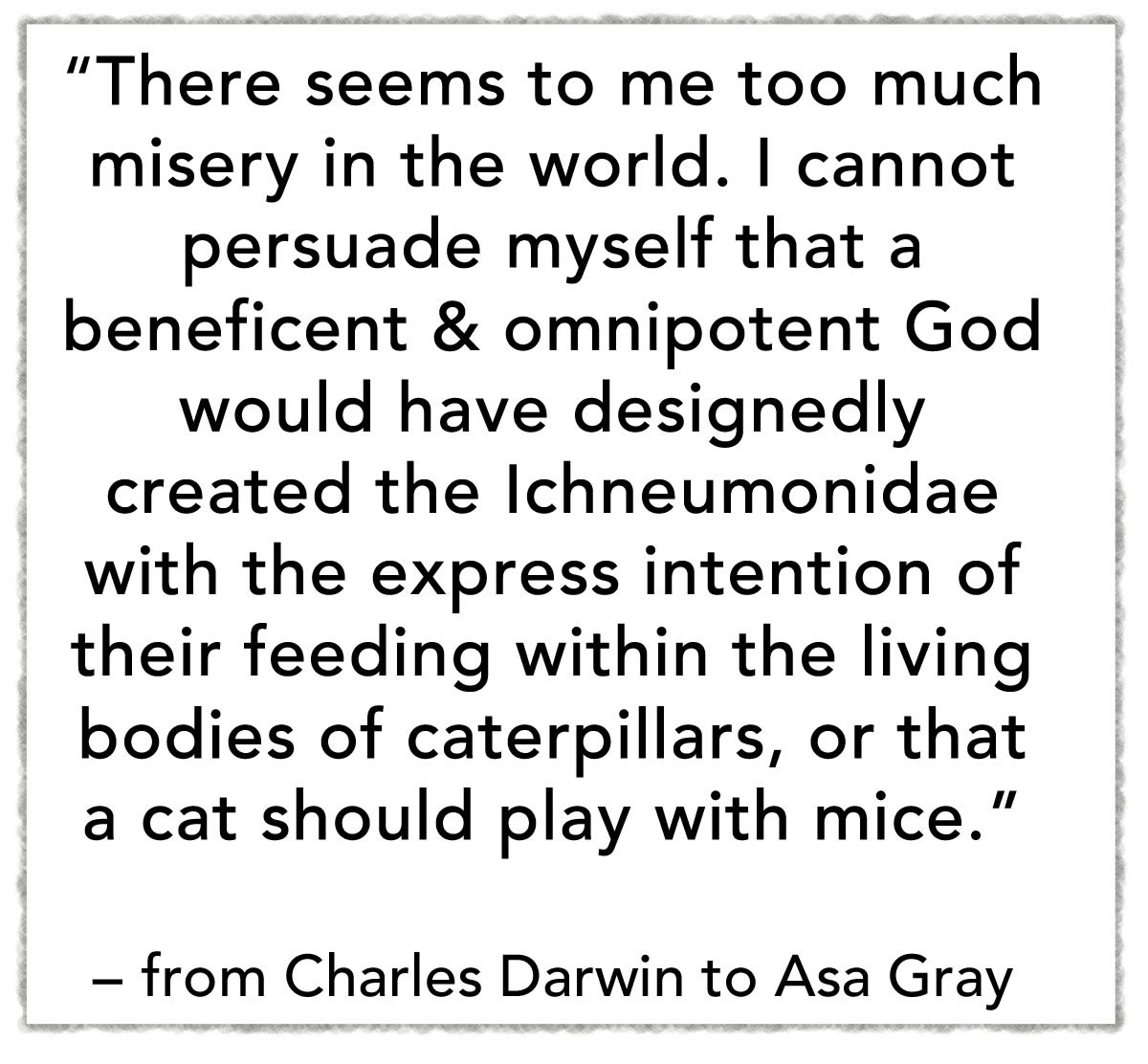

d that is absurdly old and excessively vast. Such arguments echo the view that God had no choice other than whether to create or not; that for all its flaws, evils, and unnecessary suffering this is, as posited by Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) and satirized by Voltaire (1694–1778) in his novel Candide, the best of all possible worlds. Yet, as a member of a reasonably liberal, and periodically enlightened, society, we see it as our responsibility to ameliorate such evils, to care for the weak, the sick, and the damaged and to improve human existence; to address prejudice and political manipulations [

d that is absurdly old and excessively vast. Such arguments echo the view that God had no choice other than whether to create or not; that for all its flaws, evils, and unnecessary suffering this is, as posited by Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) and satirized by Voltaire (1694–1778) in his novel Candide, the best of all possible worlds. Yet, as a member of a reasonably liberal, and periodically enlightened, society, we see it as our responsibility to ameliorate such evils, to care for the weak, the sick, and the damaged and to improve human existence; to address prejudice and political manipulations [

pecialized professional science organizations, including the

pecialized professional science organizations, including the

entalist communism seems particularly good at addressing. Similarly the lack of any demonstrable connection between

entalist communism seems particularly good at addressing. Similarly the lack of any demonstrable connection between  ical and the partisan(see:

ical and the partisan(see: