as long as teachers understand the science and its historical context

The role of science in modern societies is complex. Science-based observations and innovations drive a range of economically important, as well as socially disruptive, technologies. Many opinion polls indicate that the American public “supports” science, while at the same time rejecting rigorously established scientific conclusions on topics ranging from the safety of genetically modified organisms and the role of vaccines in causing autism to the effects of burning fossil fuels on the global environment [Pew: Views on science and society]. Given that a foundational principle of science is that the natural world can be explained without calling on supernatural actors, it remains surprising that a substantial majority of people appear to believe that supernatural entities are involved in human evolution [as reported by the Gallup organization]; although the theistic percentage has been dropping (a little) of late.

This situation highlights the fact that when science intrudes on the personal or the philosophical (within which I include the theological and the ideological), many people are willing to abandon the discipline of science to embrace explanations based on personal beliefs. These include the existence of a supernatural entity that cares for people, at least enough to create them, and that there are reasons behind life’s tragedies.

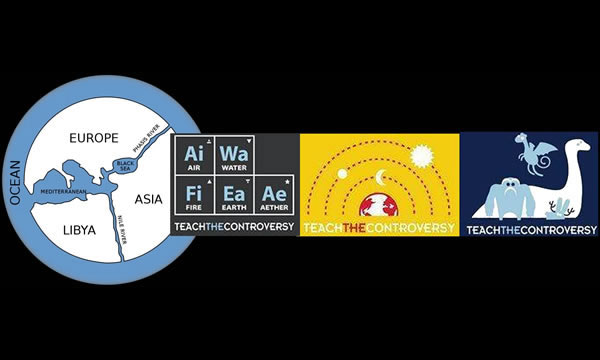

Where science appears to conflict with various non-scientific positions, the public has pushed back and rejected the scientific. This is perhaps best represented by the recent spate of “teach the controversy” legislative efforts, primarily centered on evolutionary theory and the realities of anthropogenic climate change [see Nature: Revamped ‘anti-science’ education bills]. We might expect to see, on more politically correct campuses, similar calls for anti-GMO, anti-vaccination, or gender-based curricula. In the face of the disconnect between scientific and non-scientific (philosophical, ideological, theological) personal views, I would suggest that an important part of the problem has didaskalogenic roots; that is, it arises from the way science is taught – all too often expecting students to memorize terms and master various heuristics (tricks) to answer questions rather than developing a self-critical understanding of ideas, their origins, supporting evidence, limitations, and practice in applying them.

Science is a social activity, based on a set of accepted core assumptions; it is not so much concerned with Truth, which could, in fact, be beyond our comprehension, but rather with developing a universal working knowledge, composed of ideas based on empirical observations that expand in their explanatory power over time to allow us to predict and manipulate various phenomena. Science is a product of society rather than isolated individuals, but only rarely is the interaction between the scientific enterprise and its social context articulated clearly enough so that students and the general public can develop an understanding of how the two interact. As an example, how many people appreciate the larger implications of the transition from an Earth to a Sun- or galaxy-centered cosmology? All too often students are taught about this transition without regard to its empirical drivers and philosophical and sociological implications, as if the opponents at the time were benighted religious dummies. Yet, how many students or their teachers appreciate that as originally presented the Copernican system had more hypothetical epicycles and related Rube Goldberg-esque kludges, introduced to make the model accurate, than the competing Ptolemic Sun-centered system? Do students understand how Kepler’s recognition of elliptical orbits eliminated the need for such artifices and set the stage for Newtonian physics? And how did the expulsion of humanity from the center to the periphery of things influence peoples’ views on humanity’s role and importance?

So how can education adapt to better help students and the general public develop a more realistic understanding of how science works? To my mind, teaching the controversy is a particularly attractive strategy, on the assumption that teachers have a strong grounding in the discipline they are teaching, something that many science degree programs do not achieve, as discussed below. For example, a common attack against evolutionary mechanisms relies on a failure to grasp the power of variation, arising from stochastic processes (mutation), coupled to the power of natural, social, and sexual selection. There is clear evidence that people find stochastic processes difficult to understand and accept [see Garvin-Doxas & Klymkowsky & Fooled by Randomness]. An instructor who is not aware of the educational challenges associated with grasping stochastic processes, including those central to evolutionary change, risks the same hurdles that led pre-molecular biologists to reject natural selection and turn to more “directed” processes, such as orthogenesis [see Bowler: The eclipse of Darwinism & Wikipedia]. Presumably students are even more vulnerable to intelligent-design creationist arguments centered around probabilities.

The fact that single cell measurements enable us to visualize biologically meaningful stochastic processes makes designing course materials to explicitly introduce such processes easier [Biology education in the light of single cell/molecule studies]. An interesting example is the recent work on visualizing the evolution of antibiotic resistance macroscopically [see The evolution of bacteria on a “mega-plate” petri dish].

To be in a position to “teach the controversy” effectively, it is critical that students understand how science works, specifically its progressive nature, exemplified through the process of generating and testing, and where necessary, rejecting or revising, clearly formulated and predictive hypotheses – a process antithetical to a Creationist (religious) perspective [a good overview is provided here: Using creationism to teach critical thinking]. At the same time, teachers need a working understanding of the disciplinary foundations of their subject, its core observations, and their implications. Unfortunately, many are called upon to teach subjects with which they may have only a passing familiarity. Moreover, even majors in a subject may emerge with a weak understanding of foundational concepts and their origins – they may be uncomfortable teaching what they have learned. While there is an implicit assumption that a college curriculum is well designed and effective, there is often little in the way of objective evidence that this is the case. While many of our dedicated teachers (particularly those I have met as part of the CU Teach program) work diligently to address these issues on their own, it is clear that many have not been exposed to a critical examination of the empirical observations and experimental results upon which their discipline is based [see Biology teachers often dismiss evolution & Teachers’ Knowledge Structure, Acceptance & Teaching of Evolution]. Many is the molecular biology department that does not require formal coursework in basic evolutionary mechanisms, much less a thorough consideration of natural, social, and sexual selection, and non-adaptive mechanisms, such as those associated with founder effects, population bottlenecks, and genetic drift, stochastic processes that play a key role in the evolution of many species, including humankind. Similarly, more ecologically- and physiologically-oriented majors are often “afraid” of the molecular foundations of evolutionary processes. As part of an introductory chemistry curriculum redesign project (CLUE), Melanie Cooper and her group at Michigan State University have found that students in conventional courses often fail to grasp key concepts, and that subsequent courses can sometimes fail to remediate the didaskalogenic damage done in earlier courses [see: an Achilles Heel in Chemistry Education].

The importance of a historical perspective: The power of scientific explanations are obvious, but they can become abstract when their historical roots are forgotten, or never articulated. A clear example is that the value of vaccination is obvious in the presence of deadly and disfiguring diseases. In their absence, due primarily to the effectiveness of wide-spread vaccination, the value of vaccination can be called into question, resulting in the avoidable re-emergence of these diseases. In this context, it would be important that students understand the dynamics and molecular complexity of biological systems, so that they can explain why it is that all drugs and treatments have potential side-effects, and how each individual’s genetic background influences these side-effects (although in the case of vaccination, such side effects do not include autism).

Often “controversy” arises when scientific explanations have broader social, political, or philosophical implications. Religious objections to evolutionary theory arise primarily, I believe, from the implication that we (humans) are not the result of a plan, created or evolved, but rather that we are accidents of mindless, meaningless, and often gratuitously cruel processes. The idea that our species, which emerged rather recently (that is, a few million years ago) on a minor planet on the edge of an average galaxy, in a universe that popped into existence for no particular reason or purpose ~14 billion years ago, can have disconcerting implications [link]. Moreover, recognizing that a “small” change in the trajectory of an asteroid could change the chance that humanity ever evolved [see: Dinosaur asteroid hit ‘worst possible place’] can be sobering and may well undermine one’s belief in the significance of human existence. How does it impact our social fabric if we are an accident, rather than the intention of a supernatural being or the inevitable product of natural processes?

Yet, as a person who firmly believes in the French motto of liberté, égalité, fraternité and laïcité, I feel fairly certain that no science-based scenario on the origin and evolution of the universe or life, or the implications of sexual dimorphism or “racial” differences, etc, can challenge the importance of our duty to treat others with respect, to defend their freedoms, and to insure their equality before the law. Which is not to say that conflicts do not inevitably arise between different belief systems – in my own view, patriarchal oppression needs to be called out and actively opposed where ever it occurs, whether in Saudi Arabia or on college campuses (e.g. UC Berkeley or Harvard).

![]() This is not to say that presenting the conflicts between scientific explanations of phenomena and non-scientific, but more important beliefs, such as equality under the law, is easy. When considering a number of natural cruelties, Charles Darwin wrote that evolutionary theory would claim that these are “as small consequences of one general law, leading to the advancement of all organic beings, namely, multiply, vary, let the strongest live and the weakest die” – note the absence of any reference to morality, or even sympathy for the “weakest”. In fact, Darwin would have argued that the apparent, and overt cruelty that is rampant in the “natural” world is evidence that God was forced by the laws of nature to create the world the way it is, presumably a worl

This is not to say that presenting the conflicts between scientific explanations of phenomena and non-scientific, but more important beliefs, such as equality under the law, is easy. When considering a number of natural cruelties, Charles Darwin wrote that evolutionary theory would claim that these are “as small consequences of one general law, leading to the advancement of all organic beings, namely, multiply, vary, let the strongest live and the weakest die” – note the absence of any reference to morality, or even sympathy for the “weakest”. In fact, Darwin would have argued that the apparent, and overt cruelty that is rampant in the “natural” world is evidence that God was forced by the laws of nature to create the world the way it is, presumably a worl d that is absurdly old and excessively vast. Such arguments echo the view that God had no choice other than whether to create or not; that for all its flaws, evils, and unnecessary suffering this is, as posited by Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) and satirized by Voltaire (1694–1778) in his novel Candide, the best of all possible worlds. Yet, as a member of a reasonably liberal, and periodically enlightened, society, we see it as our responsibility to ameliorate such evils, to care for the weak, the sick, and the damaged and to improve human existence; to address prejudice and political manipulations [thank you Supreme Court for ruling against race-based redistricting]. Whether anchored by philosophical or religious roots, many of us are driven to reject a scientific (biological) quietism (“a theology and practice of inner prayer that emphasizes a state of extreme passivity”) by actively manipulating our social, political, and physical environment and striving to improve the human condition, in part through science and the technologies it makes possible.

d that is absurdly old and excessively vast. Such arguments echo the view that God had no choice other than whether to create or not; that for all its flaws, evils, and unnecessary suffering this is, as posited by Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) and satirized by Voltaire (1694–1778) in his novel Candide, the best of all possible worlds. Yet, as a member of a reasonably liberal, and periodically enlightened, society, we see it as our responsibility to ameliorate such evils, to care for the weak, the sick, and the damaged and to improve human existence; to address prejudice and political manipulations [thank you Supreme Court for ruling against race-based redistricting]. Whether anchored by philosophical or religious roots, many of us are driven to reject a scientific (biological) quietism (“a theology and practice of inner prayer that emphasizes a state of extreme passivity”) by actively manipulating our social, political, and physical environment and striving to improve the human condition, in part through science and the technologies it makes possible.

At the same time, introducing social-scientific interactions can be fraught with potential controversies, particularly in our excessively politicized and self-righteous society. In my own introductory biology class (biofundamentals), we consider potentially contentious issues that include sexual dimorphism and selection and social evolutionary processes and their implications. As an example, social systems (and we are social animals) are susceptible to social cheating and groups develop defenses against cheaters; how such biological ideas interact with historical, political and ideological perspectives is complex, and certainly beyond the scope of an introductory biology course, but worth acknowledging [PLoS blog link].

In a similar manner, we understand the brain as an evolved cellular system influenced by various experiences, including those that occur during development and subsequent maturation. Family life interacts with genetic factors in a complex, and often unpredictable way, to shape behaviors. But it seems unlikely that a free and enlightened society can function if it takes seriously the premise that we lack free-will and so cannot be held responsible for our actions, an idea of some current popularity [see Free will could all be an illusion ]. Given the complexity of biological systems, I for one am willing to embrace the idea of constrained free will, no matter what scientific speculations are currently in vogue [but see a recent video by Sabine Hossenfelder You don’t have free will, but don’t worry, which has me rethinking].

Recognizing the complexities of biological systems, including the brain, with their various adaptive responses and feedback systems can be challenging. In this light, I am reminded of the contrast between the Doomsday scenario of Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, and the data-based view of the late Hans Rosling in Don’t Panic – The Facts About Population.

All of which is to say that we need to see science not as authoritarian, telling us who we are or what we should do, but as a tool to do what we think is best and why it might be difficult to achieve. We need to recognize how scientific observations inform and may constrain, but do not dictate our decisions. We need to embrace the tentative, but strict nature of the scientific enterprise which, while it cannot arrive at “Truth” can certainly identify non-sense.

Minor edits and updates and the addition of figures that had gone missing – 20 October 2020

The problem is really two-fold. One is the problem in less robust science education that you’ve outlined here, but the other is a virtually non-existent education in philosophy.

There is no good reason to believe the naturalist-materialist, Scientistic proposition that science has epistemological primacy (in fact, it is a self-contradictory axiom), so we automatically fail if we refuse to discuss the limitations of science and its inadequacies in questions of morals, politics, aesthetics, relationships, spirituality, etc. Without doing so, we implicitly teach science as an authoritarian system which WILL be rejected, as you note, when it conflicts with lived moral, political, aesthetic, relational, spiritual, etc. experience. You do it yourself, in your confession of ideological dogmatism: “Yet, as a person who firmly believes in the French motto of liberté, égalité, fraternité, laïcité, I feel fairly certain that no science-based scenario on the origin and evolution of the universe or life, or the implications of sexual dimorphism or racial differences, etc, can challenge the importance of our duty to treat others with respect, to defend their freedoms, and to insure their equality before the law.” You express disapproval over philosophies of theistic evolution while at the same time refusing to entertain the implications of a purely materialistic science for your own liberalism.

Without a good grounding in philosophy, we don’t equip students to adequately and effectively integrate the findings and methods of science into a holistic worldview. We just sort of leave them to go off, higgledy-piggledy accepting some things and rejecting other things in a nearly arbitrary fashion as suits their existing worldview, like rejecting vaccines or believing in ephemeral things like “equality” and “freedom” and “duty” and “respect”. We’d be much better off giving students the philosophical tools to make sense of science and its findings and its limitations, and to work out the implications of that logically and consistently. Why we DON’T do that is a whole other big issue…

LikeLike

By coincidence I just started a project to facilitate teaching the climate debate.

See https://www.gofundme.com/climate-change-debate-education.

Teaching any contemporary scientific debate is difficult in K-12 and most undergraduate college courses, because science is taught as a body of established and fixed knowledge. There are no debates in the textbooks, except historical ones. It is typically only at the Masters degree level that one gets to the point where the ongoing debates are studied. This is a fundamental problem with science education, quite apart from the specific issues mentioned in this article.

LikeLike

If students were taught all of the facts about evolution they would understand that evolution is more impossible than the Tooth Fairy, Santa Claus, and the Headless Horseman. See http://originalitythroughouttheuniverse.com/life-science-trial/ for a list of bluffing evolutionists.

LikeLike

Oh, I think not – but perhaps you have not been introduced into the full range of evolutionary mechanisms. Perhaps you might want to read the evolution sections of biofundamentals: http://tinyurl.com/nvfo97h

LikeLike

It should be noted ID advocate Sarah Chaffee has riffed off your piece https://evolutionnews.org/2017/06/sure-teach-the-controversy-says-an-evolutionist-but-you-know-whats-coming-next/?utm_content=bufferdadbf&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer skipping your content in favor of highlighting Gross’ bit.

The essence of sound science and history involves some basic methods rules:

Paying attention to all the data, at primary source level, and attempting to work out a detailed explanatory framework to account for those data, along with criteria for accepting or rejecting the model being proposed. In my #TIP project at http://www.tortucan.wordpress.com I study how those basic methods rules are violated in the antievolutionism subculture, which bumps into barely 10% of the relevant data and doesn’t even try to account for that slim subset in terms of their vague hypotheses, plus the fact that none of the antievolutionists (including Chaffee) ever lay out criteria for evidence they would allow as disconfirming their notions.

LikeLike

Well, that is ok. The issue with creationism/Intelligent Designers is that their view explains nothing, predicts nothing, and is just not useful for a working scientist; it is distraction that can so easily refuted that it is waste of time to consider it.

LikeLike

Its not about truth? sure it is! science is about conclusions that are accurate conclusions. TRUTH!

Rejection of evolutionism or creationism ideas is based on conclusions that are historic. Mankind’s conclusion that complexity and diversity must of been made by a great thinking being.

Right or wrong its a legitimate hypothesis to start with.

Then in the modern world, since the reformation, conclusions are based on the bible especially genesis in origin stuff.

The bible is presented, and accepted, as a witness to origins of this and that.

If alternatives come up then they are addressed.

there is nothing, nor any intellectual or moral persuasive points, to say creationists, hundreds of millions in Amertica are anti-science or don’t understand science.

Its a contention about a few conclusions touching on origin subjects and creationism is increasingly more successful as articles like this prove by having to be written and published. this never happened until the 1980’s.

The modern censorship movement does include creationism becvause its about God/Christian beliefs/conclusions.

If one side is censored then that means its officially been settled its not true or if , a option, of being true then truth is not the objective in science. AN ABSURDITY!

censorship is a reflection on the censer’s motivations and its always the same. To stop opposition to a conclusion(s) from the conclusion being censored. To stop public reflection on equal terms in public institutions.

How is it doing? If there was no censorship of creationism would Creationism be EVEN GREATER in stats?? Is this a conclusion in board meetings at censorship headquarters?

LikeLike