The other day, through no fault of my own, I found myself looking at the courses required by our molecular biology undergraduate degree program. I discovered a requirement for a 5 credit hour physics course, and a recommendation that this course be taken in the students’ senior year – a point in their studies when most have already completed their required biology courses. Befuddlement struck me, what was the point of requiring an introductory physics course in the context of a molecular biology major? Was this an example of time-travel (via wormholes or some other esoteric imagining) in which a physics course in the future impacts a students’ understanding of molecular biology in the past? I was also struck by the possibility that requiring such a course in the students’ senior year would measurably impact their time to degree.

In a search for clarity and possible enlightenment, I reflected back on my own experiences in an undergraduate biophysics degree program – as a practicing cell and molecular biologist, I was somewhat confused. I could not put my finger on the purpose of our physics requirement, except perhaps the admirable goal of supporting physics graduate students. But then, after feverish reflections on the responsibilities of faculty in the design of the courses and curricula they prescribe for their students and the more general concepts of instructional (best) practice and malpractice, my mind calmed, perhaps because I was distracted by an article on Oxford Nanopore’s MinION (↓), a “portable real-time device for DNA and RNA sequencing”,a device that plugs into the USB port on one’s laptop!

Distracted from the potentially quixotic problem of how to achieve effective educational reform at the undergraduate level, I found myself driven on by an insatiable curiosity (or a deep-seated insecurity) to insure that I actually understood how this latest generation of DNA sequencers worked. This led me to a paper by Meni Wanunu (2012. Nanopores: A journey towards DNA sequencing)[1]. On reading the paper, I found myself returning to my original belief, yes, understanding physics is critical to developing a molecular-level understanding of how biological systems work, BUT it was just not the physics normally inflicted upon (required of) students [2]. Certainly this was no new idea. Bruce Alberts had written on this topic a number of times, most dramatically in his 1989 paper “The cell as a collection of molecular machines” [3]. Rather sadly, and not withstanding much handwringing about the importance of expanding student interest in, and understanding of, STEM disciplines, not much of substance in this area has occurred. While (some minority of) physics courses may have adopted active engagement pedagogies (in the meaning of Hake [4]) most insist on teaching macroscopic physics, rather than to focus on, or even to consider, the molecular level physics relevant to biological systems, explicitly the physics of protein machines in a cellular (biological) context. Why sadly, because conventional, that is non-biologically relevant introductory physics and chemistry courses, all to often serve the role of a hazing ritual, driving many students out of biology-based careers [5], in part I suspect, because they often seem irrelevant to students’ interests in the workings of biological systems. (footnote 1)

Nanopore’s sequencer and Wanunu’s article (footnote 2) got me thinking again about biological machines, of which there are a great number, ranging from pumps, propellers, and oars to various types of transporters, molecular truckers that move chromosomes, membrane vesicles, and parts of cells with respect to one another, to DNA detanglers, protein unfolders, and molecular recyclers (↓).

Nanopore’s sequencer works based on the fact that as a single strand of DNA (or RNA) moves through a narrow pore, the different bases (A,C,T,G) occlude the pore to different extents, allowing different numbers of ions, different amounts of current, to pass through the pore. These current differences can be detected, and allows for a nucleotide sequence to be “read” as the nucleic acid strand moves through the pore. Understanding the process involves understanding how molecules move, that is the physics of molecular collisions and energy transfer, how proteins and membranes allow and restrict ion movement, and the impact of chemical gradients and electrical fields across a membrane on molecular movements – all physical concepts of widespread significance in biological systems (here is an example of where a better understanding of physics could be useful to biologists). Such ideas can be extended to the more general questions of how molecules move within the cell, and the effects of molecular size and inter-molecular interactions within a concentrated solution of proteins, protein polymers, lipid membranes, and nucleic acids, such as described in Oliverira et al., (2016 Increased cytoplasmic viscosity hampers aggregate polar segregation in Escherichia coli)[6]. At the molecular level, the processes, while biased by electric fields (potentials) and concentration gradients, are stochastic (noisy). Understanding of stochastic processes is difficult for students [7], but critical to developing an appreciation of how such processes can lead to phenotypic differences between cells with the same genotypes (previous post) and how such noisy processes are managed by the cell and within a multicellular organism.

As path leads on to path, I found myself considering the (←) spear-chucking protein machine present in the pathogenic bacteria Vibrio cholerae; this molecular machine is used to inject toxins into neighbors that the bacterium happens to bump into (see Joshi et al., 2017. Rules of Engagement: The Type VI Secretion System in Vibrio cholerae)[8]. The system is complex and acts much like a spring-loaded and rather “inhumane” mouse trap. This is one of a number of bacterial type VI systems, and “has structural and functional homology to the T4 bacteriophage tail spike and tube” – the molecular machine that injects bacterial cells with the virus’s genetic material, its DNA.

Building the bacterium’s spear-based injection system is control by a social (quorum sensing) system, a way that unicellular organisms can monitor whether they are alone or living in an environment crowded with other organisms. During the process of assembly, potential energy, derived from various chemically coupled, thermodynamically favorable reactions, is stored in both type VI “spears” and the contractile (nucleic acid injecting) tails of the bacterial viruses (phage). Understanding the energetics of this process, exactly how coupling thermodynamically favorable chemical reactions, such as ATP hydrolysis, or physico-chemical reactions, such as the diffusion of ions down an electrochemical gradient, can be used to set these “mouse traps”, and where the energy goes when the traps are sprung is central to students’ understanding of these and a wide range of other molecular machines.

Energy stored in such molecular machines during their assembly can be used to move the cell. As an example, another bacterial system generates contractile (type IV pili) filaments; the contraction of such a filament can allow “the bacterium to move 10,000 times its own body weight, which results in rapid movement” (see Berry & Belicic 2015. Exceptionally widespread nanomachines composed of type IV pilins: the prokaryotic Swiss Army knives)[9]. The contraction of such a filament has been found to be used to import DNA into the cell, an early step in the process of horizontal gene transfer. In other situations (other molecular machines) such protein filaments access thermodynamically favorable processes to rotate, acting like a propeller, driving cellular movement.

During my biased random walk through the literature, I came across another, but molecularly distinct, machine used to import DNA into Vibrio (see Matthey & Blokesch 2016. The DNA-Uptake Process of Naturally Competent Vibrio cholerae)[10].

This molecular machine enables the bacterium to import DNA from the environment, released, perhaps, from a neighbor killed by its spear. In this system (←), the double stranded DNA molecule is first transported through the bacterium’s outer membrane; the DNA’s two strands are then separated, and one strand passes through a channel protein through the inner (plasma) membrane, and into the cytoplasm, where it can interact with the bacterium’s genomic DNA.

The value of introducing students to the idea of molecular machines is that it helps to demystify how biological systems work, how such machines carry out specific functions, whether moving the cell or recognizing and repairing damaged DNA. If physics matters in biological curriculum, it matters for this reason – it establishes a core premise of biology, namely that organisms are not driven by “vital” forces, but by prosaic physiochemical ones. At the same time, the molecular mechanisms behind evolution, such as mutation, gene duplication, and genomic reorganization provide the means by which new structures emerge from pre-existing ones, yet many is the molecular biology degree program that does not include an introduction to evolutionary mechanisms in its required course sequence – imagine that, requiring physics but not evolution? (see [11]).

One final point regarding requiring students to take a biologically relevant physics course early in their degree program is that it can be used to reinforce what I think is a critical and often misunderstood point. While biological systems rely on molecular machines, we (and by we I mean all organisms) are NOT machines, no matter what physicists might postulate -see We Are All Machines That Think. We are something different and distinct. Our behaviors and our feelings, whether ultimately understandable or not, emerge from the interaction of genetically encoded, stochastically driven non-equilibrium systems, modified through evolutionary, environmental, social, and a range of unpredictable events occurring in an uninterrupted, and basically undirected fashion for ~3.5 billion years. While we are constrained, we are more, in some weird and probably ultimately incomprehensible way.

Footnotes:

[1] A discussion with Melanie Cooper on what chemistry is relevant to a life science major was a critical driver in our collaboration to develop the chemistry, life, the universe, and everything (CLUE) chemistry curriculum.

[2] Together with my own efforts in designing the biofundamentals introductory biology curriculum.

literature cited

1. Wanunu, M., Nanopores: A journey towards DNA sequencing. Physics of life reviews, 2012. 9(2): p. 125-158.

2. Klymkowsky, M.W. Physics for (molecular) biology students. 2014 [cited 2014; Available from: http://www.aps.org/units/fed/newsletters/fall2014/molecular.cfm.

3. Alberts, B., The cell as a collection of protein machines: preparing the next generation of molecular biologists. Cell, 1998. 92(3): p. 291-294.

4. Hake, R.R., Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: a six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. Am. J. Physics, 1998. 66: p. 64-74.

5. Mervis, J., Weed-out courses hamper diversity. Science, 2011. 334(6061): p. 1333-1333.

6. Oliveira, S., R. Neeli‐Venkata, N.S. Goncalves, J.A. Santinha, L. Martins, H. Tran, J. Mäkelä, A. Gupta, M. Barandas, and A. Häkkinen, Increased cytoplasm viscosity hampers aggregate polar segregation in Escherichia coli. Molecular microbiology, 2016. 99(4): p. 686-699.

7. Garvin-Doxas, K. and M.W. Klymkowsky, Understanding Randomness and its impact on Student Learning: Lessons from the Biology Concept Inventory (BCI). Life Science Education, 2008. 7: p. 227-233.

8. Joshi, A., B. Kostiuk, A. Rogers, J. Teschler, S. Pukatzki, and F.H. Yildiz, Rules of engagement: the type VI secretion system in Vibrio cholerae. Trends in microbiology, 2017. 25(4): p. 267-279.

9. Berry, J.-L. and V. Pelicic, Exceptionally widespread nanomachines composed of type IV pilins: the prokaryotic Swiss Army knives. FEMS microbiology reviews, 2014. 39(1): p. 134-154.

10. Matthey, N. and M. Blokesch, The DNA-uptake process of naturally competent Vibrio cholerae. Trends in microbiology, 2016. 24(2): p. 98-110.

11. Pallen, M.J. and N.J. Matzke, From The Origin of Species to the origin of bacterial flagella. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2006. 4(10): p. 784-90.

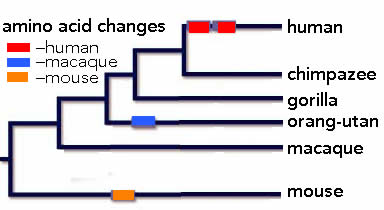

these two amio acid changes alter the activity of the human protein, that is the ensemble of genes that it regulates. That foxp2 has an important role in humans was revealed through studies of individuals in a family that displayed a severe language disorder linked to a mutation that disrupts the function of the foxp2 protein. Individuals carrying this mutant foxp2 allele display speech apraxia, a “severe impairment in the selection and sequencing of fine oral and facial movements, the ability to break up words into their constituent phonemes, and the production and comprehension of word inflections and syntax” (cited in

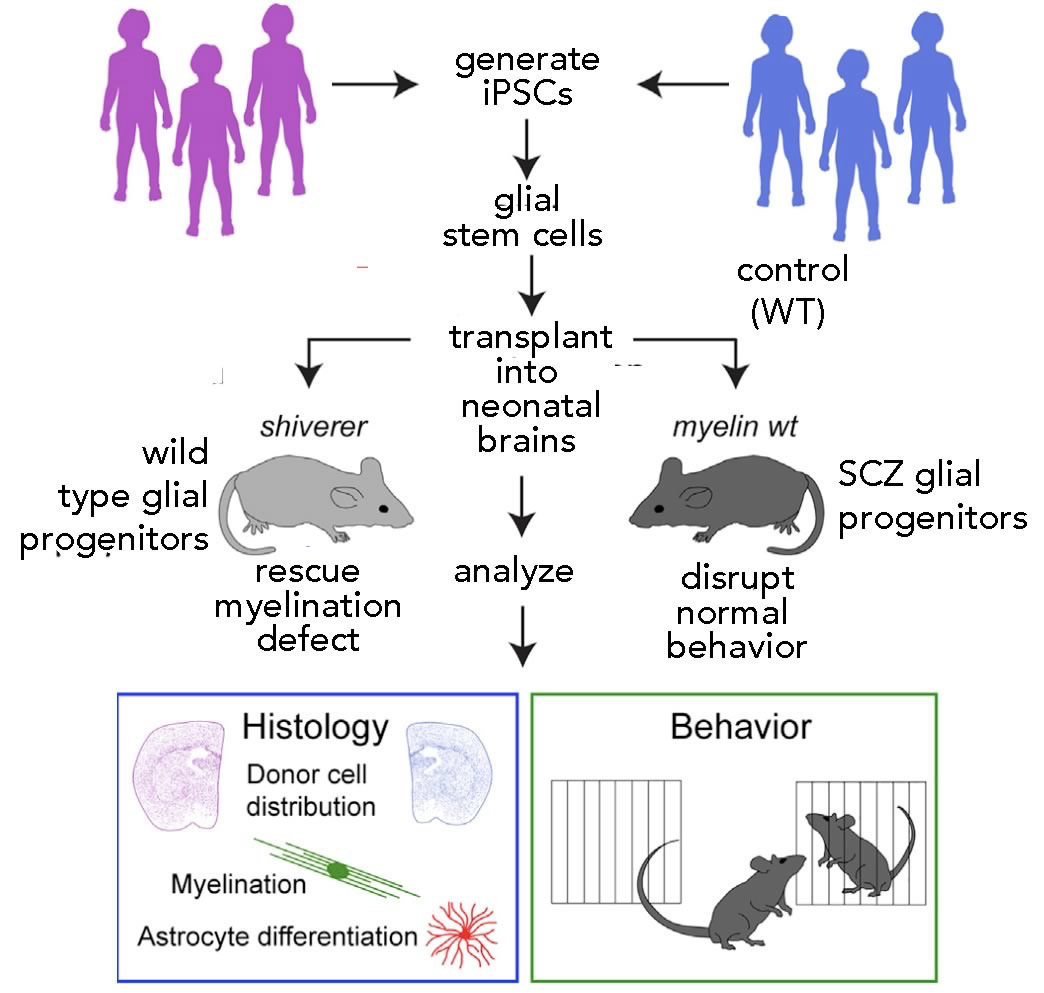

these two amio acid changes alter the activity of the human protein, that is the ensemble of genes that it regulates. That foxp2 has an important role in humans was revealed through studies of individuals in a family that displayed a severe language disorder linked to a mutation that disrupts the function of the foxp2 protein. Individuals carrying this mutant foxp2 allele display speech apraxia, a “severe impairment in the selection and sequencing of fine oral and facial movements, the ability to break up words into their constituent phonemes, and the production and comprehension of word inflections and syntax” (cited in  Glial cells are the major non-neuronal component of the central nervous system. Once thought of as passive “support” cells, it is now clear that the two major types of glia, known as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, play a number of important roles in neural functioning [

Glial cells are the major non-neuronal component of the central nervous system. Once thought of as passive “support” cells, it is now clear that the two major types of glia, known as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, play a number of important roles in neural functioning [ Subsequently, Goldman and associates used a variant of this approach to introduce hGPCs (derived from human embryonic stem cells) carrying either a normal or mutant version of the Huntingtin protein, a protein associated with the severe neural disease Huntington’s chorea (OMIM:

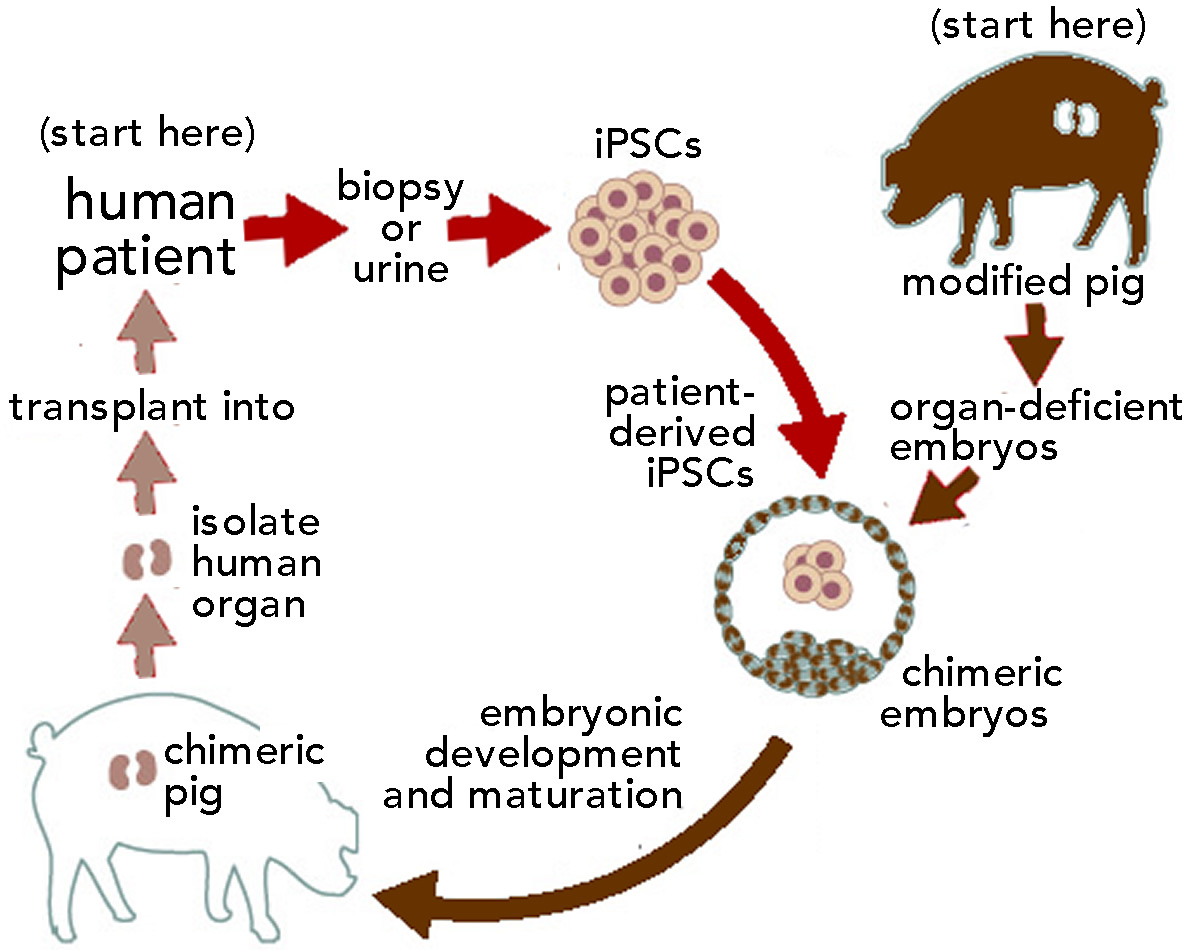

Subsequently, Goldman and associates used a variant of this approach to introduce hGPCs (derived from human embryonic stem cells) carrying either a normal or mutant version of the Huntingtin protein, a protein associated with the severe neural disease Huntington’s chorea (OMIM:  The second obstacle to pig → human transplantation is the presence of retroviruses within the pig genome. All vertebrate genomes, including those of humans, contain many inserted retroviruses; almost 50% of the human genome is retrovirus-derived sequence (an example of unintelligent design if ever there was one). Most of these endogenous retroviruses are “under control” and are normally benign (see

The second obstacle to pig → human transplantation is the presence of retroviruses within the pig genome. All vertebrate genomes, including those of humans, contain many inserted retroviruses; almost 50% of the human genome is retrovirus-derived sequence (an example of unintelligent design if ever there was one). Most of these endogenous retroviruses are “under control” and are normally benign (see  or eyes can be generated. In an embryo that cannot make these organs, which can be a lethal defect, the introduction of stem cells from an animal that can form these organs can lead to the formation of an organ composed primarily of cells derived from the transplanted (human) cells.

or eyes can be generated. In an embryo that cannot make these organs, which can be a lethal defect, the introduction of stem cells from an animal that can form these organs can lead to the formation of an organ composed primarily of cells derived from the transplanted (human) cells.