Montaigne concludes, like Socrates, that ignorance aware of itself is the only true knowledge” – from “forbidden knowledge” by Roger Shattuck

A month or so ago we were treated to a flurry of media excitement surrounding the release of the latest Pew Research survey on Americans’ scientific knowledge. The results of such surveys have been interpreted to mean many things. As an example, the title of Maggie Koerth-Baker’s short essay for the 538 web site was a surprising “Americans are Smart about Science”, a conclusion not universally accepted (see also). Koerth-Baker was taken by the observation that the survey’s results support a conclusion that Americans’ display “pretty decent scientific literacy”. Other studies (see Drummond & Fischhoff 2017) report that one’s ability to recognize scientifically established statements does not necessarily correlate with the acceptance of science policies – on average climate change “deniers” scored as well on the survey as “acceptors”. In this light, it is worth noting that science-based policy pronouncements generally involve projections of what the future will bring, rather than what exactly is happening now. Perhaps more surprisingly, greater “science literacy” correlates with more polarized beliefs that, given the tentative nature of scientific understanding –which is not about truth per se but practical knowledge–suggests that the surveys’ measure something other than scientific literacy. While I have written on the subject before it seems worth revisiting – particularly since since then I have read Rosling’s FactFullness and thought more about the apocalyptic bases of many secular and religious movements, described in detail by the historian Norman Cohn and the philosopher John Gray and gained a few, I hope, potentially useful insights on the matter.

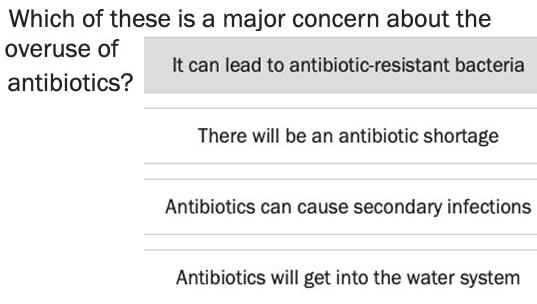

First, to understand what the survey reports we should take a look at the questions asked and decide what the ability to chose correctly implies about scientific literacy, as generally claimed, or something simpler – perhaps familiarity. It is worth recognizing that all such instruments, particularly those that are multiple choice in format, are proxies for a more detailed, time consuming, and costly Socratic interrogation designed to probe the depth of a persons’ knowledge and understanding. In the Pew (and most other such surveys) choosing the correct response implies familiarity with various topics impacted by scientific observations. They do not necessarily reveal whether or not the respondent understands where the ideas come from, why they are the preferred response, or exactly where and when they are relevant (2). So is “getting the questions correct” demonstrates a familiarity with the language of science and some basic observations and principles but not the limits of respondents’ understanding.

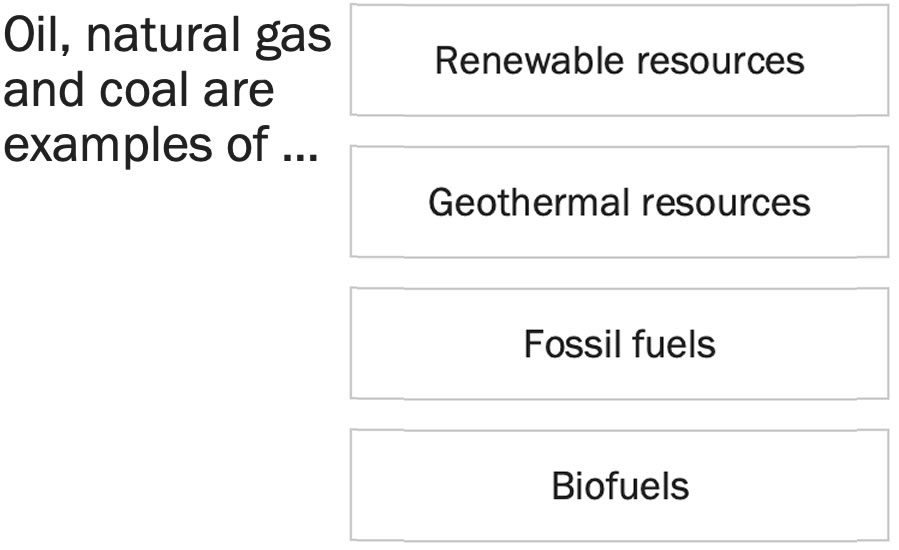

Take for example the question on antibiotic resistance (→). The correct answer “it can lead to antibiotic-resistant bacteria” does not reveal whether the respondent understands the evolutionary (selective) basis for this effect, that is random mutagenesis (or horizontal gene transfer) and antibiotic-resistance based survival. It is imaginable that a fundamentalist religious creationist could select the correct answer based on plausible, non-evolutionary mechanisms (3). In a different light, the question on oil, natural gas and coal (↓) could be seen as ambiguous – aren’t these all derived from long dead organisms, so couldn’t they reasonably be termed biofuels?

While there are issues with almost any such multiple choice survey instrument, surely we would agree that choosing the “correct” answers to these 11 questions reflects some awareness of current scientific ideas and terminologies. Certainly knowing (I think) that a base can neutralize and acid leaves unresolved how exactly the two interact, that is what chemical reaction is going on, not to mention what is going on in the stomach and upper gastrointestinal tract of a human being. In this case, selecting the correct answer is not likely to conflict with one’s view of anthropogenic effects on climate, sex versus gender, or whether one has an up to date understanding of the mechanisms of immunity and brain development, or the social dynamics behind vaccination – specifically the responsibilities that members of a social group have to one another.

But perhaps a more relevant point is our understanding of how science deals with the subject of predictions, because at the end of the day it is these predictions that may directly impact people in personal, political, and economically impactful ways.

We can, I think, usefully divide scientific predictions into two general classes. There are predictions about a system that can be immediately confirmed or dismissed through direct experiment and observation and those that cannot. The immediate (accessible) type of prediction is the standard model of scientific hypothesis testing, an approach that reveals errors or omissions in one’s understanding of a system or process. Generally these are the empirical drivers of theoretical understanding (although perhaps not in some areas of physics). The second type of prediction is inherently more problematic, as it deals with the currently unobservable future (or the distant past). We use our current understanding of the system, and various assumptions, to build a predictive model of the system’s future behavior (or past events), and then wait to see if they are confirmed. In the case of models about the past, we often have to wait for a fortuitous discovery, for example the discovery of a fossil that might support or disprove our model.

It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future

– Yogi Berra (apparently)

Anthropogenic effects on climate are an example of the second type of prediction. No matter our level of confidence, we cannot be completely sure our model is accurate until the future arrives. Nevertheless, there is a marked human tendency to take predictions, typically about the end of the world or the future of the stock market, very seriously and to make urgent decisions based upon them. In many cases, these predictions impact only ourselves, they are personal. In the case of climate change, however, they are likely to have disruptive effects that impact many. Part of the concern about study predictions is that responses to these predictions will have immediate impacts, they produce social and economic winners and losers whether or not the predictions are confirmed by events. As Hans Rosling points out in his book Factfullness, there is an urge to take urgent, drastic, and pro-active actions in the face of perceived (predicted) threats. These recurrent and urgent calls to action (not unlike repeated, and unfulfilled predictions of the apocalypse) can lead to fatigue with the eventual dismissal of important warnings; warnings that should influence albeit perhaps not dictate ecological-economic and political policy decisions.

Footnotes and literature cited:

1. As a Pew Biomedical Scholar, I feel some peripheral responsibility for the impact of these reports

2. As pointed out in a forthcoming review, the quality of the distractors, that is the incorrect choices, can dramatically impact the conclusions derived from such instruments.

3. I won’t say intelligent design creationist, as that makes no sense. Organisms are clearly not intelligently designed, as anyone familiar with their workings can attest

Drummond, C. & B. Fischhoff (2017). “Individuals with greater science literacy and education have more polarized beliefs on controversial science topics.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114: 9587-9592.