Is the popularization of science encouraging a growing disrespect for scientific expertise?

Do we need to reform science education so that students are better able to detect scientific BS?

It is common wisdom that popularizing science by exposing the public to scientific ideas is an unalloyed good, bringing benefits to both those exposed and to society at large. Many such efforts are engaging and entertaining, often taking the form of compelling images with quick cuts between excited sound bites from a range of “experts.” A number of science-centered programs, such PBS’s NOVA series, are particularly adept and/or addicted to this style. Such presentations introduce viewers to natural wonders, and often provide scientific-sounding, albeit often superficial and incomplete, explanations – they appeal to the gee-whiz and inspirational, with “mind-blowing” descriptions of how old, large, and weird the natural world appears to be. But there are darker sides to such efforts. Here I focus on one, the idea that a rigorous, realistic understanding of the scientific enterprise and its conclusions, is easy to achieve, a presumption that leads to unrealistic science education standards, and the inability to judge when scientific pronouncements are distorted or unsupported, as well as anti-scientific personal and public policy positions.![]() That accurate thinking about scientific topics is easy to achieve is an unspoken assumption that informs much of our educational, entertainment, and scientific research system. This idea is captured in the recent NYT best seller “Astrophysics for people in a hurry” – an oxymoronic presumption. Is it possible for people “in a hurry” to seriously consider the observations and logic behind the conclusions of modern astrophysics? Can they understand the strengths and weaknesses of those conclusions? Is a superficial familiarity with the words used the same as understanding their meaning and possible significance? Is acceptance understanding? Does such a cavalier attitude to science encourage unrealistic conclusions about how science works and what is known with certainty versus what remains speculation? Are the conclusions of modern science actually easy to grasp?

That accurate thinking about scientific topics is easy to achieve is an unspoken assumption that informs much of our educational, entertainment, and scientific research system. This idea is captured in the recent NYT best seller “Astrophysics for people in a hurry” – an oxymoronic presumption. Is it possible for people “in a hurry” to seriously consider the observations and logic behind the conclusions of modern astrophysics? Can they understand the strengths and weaknesses of those conclusions? Is a superficial familiarity with the words used the same as understanding their meaning and possible significance? Is acceptance understanding? Does such a cavalier attitude to science encourage unrealistic conclusions about how science works and what is known with certainty versus what remains speculation? Are the conclusions of modern science actually easy to grasp?

![]() The idea that introducing children to science will lead to an accurate grasp the underlying concepts involved, their appropriate application, and their limitations is not well supported [1]; often students leave formal education

The idea that introducing children to science will lead to an accurate grasp the underlying concepts involved, their appropriate application, and their limitations is not well supported [1]; often students leave formal education  with a fragile and inaccurate understanding – a lesson made explicit in Matt Schneps and Phil Sadler’s Private Universe videos. The feeling that one understands a topic, that science is in some sense easy, undermines respect for those who actually do understand a topic, a situation discussed in detail in Tom Nichols “The Death of Expertise.” Under-estimating how hard it can be to accurately understand a scientific topic can lead to unrealistic science standards in schools, and often the trivialization of science education into recognizing words rather than understanding the concepts they are meant to convey.

with a fragile and inaccurate understanding – a lesson made explicit in Matt Schneps and Phil Sadler’s Private Universe videos. The feeling that one understands a topic, that science is in some sense easy, undermines respect for those who actually do understand a topic, a situation discussed in detail in Tom Nichols “The Death of Expertise.” Under-estimating how hard it can be to accurately understand a scientific topic can lead to unrealistic science standards in schools, and often the trivialization of science education into recognizing words rather than understanding the concepts they are meant to convey.

The fact is, scientific thinking about most topics is difficult to achieve and maintain – that is what editors, reviewers, and other scientists, who attempt to test and extend the observations of others, are for – together they keep science real and honest. Until an observation has been repeated or confirmed by others, it can best be regarded as an interesting possibility, rather than a scientifically established fact. Moreover, until a plausible mechanism explaining the observation has been established, it remains a serious possibility that the entire phenomena will vanish, more or less quietly (think cold fusion). The disappearing physiological effects of “power posing” comes to mind. Nevertheless the incentives to support even disproven results can be formidable, particularly when there is money to be made and egos on the line. ![]()

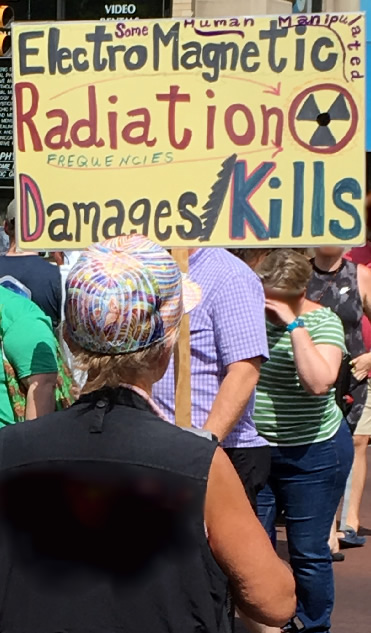

While power-posing might be helpful to some, even though physiologically useless, there are more dangerous pseudo-scientific scams out there. The gullible may buy into “raw water” (see: Raw water: promises health, delivers diarrhea) but the persistent, and in some groups growing, anti-vaccination movement continues to cause real damage to children (see Thousands of cheerleaders exposed to mumps). One can ask oneself, why haven’t professional science groups, such as the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), not called for a boycott of NETFLIX, given that NETFLIX continues to distribute the anti-scientific, anti-vaccination program VAXXED [2]? And how do Oprah Winfrey and Donald Trump [link: Oprah Spreads Pseudoscience and Trump and the anti-vaccine movement] avoid universal ridicule for giving credence to ignorant non-sense, and for disparaging the hard fought expertise of the biomedical community? A failure to accept well established expertise goes along way to understanding the situation. Instead of an appreciation for what we do and do not know about the causes of autism (see: Genetics and Autism Risk & Autism and infection), there are desperate parents who turn to a range of “therapies” promoted by anti-experts. The tragic case of parents trying to cure autism by forcing children to drink bleach (see link) illustrates the seriousness of the situation.

So why do a large percentage of the public ignore the conclusions of disciplinary experts? I would argue that an important driver is the way that science is taught and popularized [3]. Beyond the obvious fact that a range of politicians and capitalists (in both the West and the East) actively distain expertise that does not support their ideological or pecuniary positions [4], I would claim that the way we teach science, often focussing on facts rather than processes, largely ignoring the historical progression by which knowledge is established, and the various forms of critical analyses to which scientific conclusions are subjected to, combines with the way science is popularized, erodes respect for disciplinary expertise. Often our education systems fail to convey how difficult it is to attain real disciplinary expertise, in particular the ability to clearly articulate where ideas and conclusions come from and what they do and do not imply. Such expertise is more than a degree, it is a record of rigorous and productive study and useful contributions, and a critical and objective state of mind. Science standards are often heavy on facts, and weak on critical analyses of those ideas and observations that are relevant to a particular process. As Carl Sagan might say, we have failed to train students on how to critically evaluate claims, how to detect baloney (or BS in less polite terms)[5].

![]()

In the area of popularizing scientific ideas, we have allowed hype and over-simplification to capture the flag. To quote from a article by David Berlinski [link: Godzooks], we are continuously bombarded with a range of pronouncements about new scientific observations or conclusions and there is often a “willingness to believe what some scientists say without wondering whether what they say is true”, or even what it actually means. No longer is the in-depth, and often difficult and tentative explanation conveyed, rather the focus is on the flashy conclusion (independent of its plausibility). Self proclaimed experts pontificate on topics that are often well beyond their areas of training and demonstrated proficiency – many is the physicist who speaks not only about the completely speculative multiverse, but on free will and ethical beliefs. Complex and often irreconcilable conflicts between organisms, such as those between mother and fetus (see: War in the womb), male and female (in sexually dimorphic species), and individual liberties and social order, are ignored instead of explicitly recognized, and their origins understood. At the same time, there are real pressures acting on scientific researchers (and the institutions they work for) and the purveyors of news to exaggerate the significance and broader implications of their “stories” so as to acquire grants, academic and personal prestige, and clicks. Such distortions serve to erode respect for scientific expertise (and objectivity).![]()

So where are the scientific referees, the individuals that are tasked to enforce the rules of the game; to call a player out of bounds when they leave the playing field (their area of expertise) or to call a foul when rules are broken or bent, such as the fabrication, misreporting, suppression, or over-interpretation of data, as in the case of the anti-vaccinator Wakefield. Who is responsible for maintaining the integrity of the game? Pointing out the fact that many alternative medicine advocates are talking meaningless blather (see: On skepticism & pseudo-profundity)? Where are the referees who can show these charlatans the “red card” and eject them from the game?

Clearly there are no such referees. Instead it is necessary to train as large a percentage of the population as possible to be their own science referees – that is, to understand how science works, and to identify baloney when it is slung at them. When a science popularizer, whether for well meaning or self-serving reasons, steps beyond their expertise, we need to call them out of

bounds! And when scientists run up against the constraints of the scientific process, as appears to occur periodically with t heoretical physicists, and the occasional neuroscientist (see: Feuding physicists and The Soul of Science) we need to recognize the foul committed. If our educational system could help develop in students a better understanding of the rules of the scientific game, and why these rules are essential to scientific progress, perhaps we can help re-establish both an appreciation of rigorous scientific expertise, as well as a respect for what is that scientists struggle to do.

heoretical physicists, and the occasional neuroscientist (see: Feuding physicists and The Soul of Science) we need to recognize the foul committed. If our educational system could help develop in students a better understanding of the rules of the scientific game, and why these rules are essential to scientific progress, perhaps we can help re-establish both an appreciation of rigorous scientific expertise, as well as a respect for what is that scientists struggle to do.

- And is it clearly understood that they have nothing to say as to what is right or wrong.

- Similarly, many PBS stations broadcast pseudoscientific infomercials: for example see Shame on PBS, Brain Scam, and the Deepak Chopra’s anti-scientific Brain, Mind, Body, Connection, currently playing on my local PBS station. Holocaust deniers and slavery apologists are confronted much more aggressively.

- As an example, the idea that new neurons are “born” in the adult hippocampus, up to now established orthodoxy, has recently been called into question: see Study Finds No Neurogenesis in Adult Humans’ Hippocampi

- Here is a particular disturbing example: By rewriting history, Hindu nationalists lay claim to India

- Pennycook, G., J. A. Cheyne, N. Barr, D. J. Koehler and J. A. Fugelsang (2015). “On the reception and detection of pseudo-profound bullshit.” Judgment and Decision Making 10(6): 549.

Unfortunately, all too often instructors, particularly in introductory level college science courses, are not the masters of their ships; that is, they are not rewarded for generating more effective course materials. An emphasis on course “coverage” over learning, whether through peer-pressure, institutional apathy, or both, generates unnecessary obstacles to both student engagement and content mastery. To reverse the effects of the reverse DK effect, we need to encourage instructors, course designers, and departments to see the presentation of core disciplinary observations and concepts as the intellectually challenging and valuable endeavor that it is. In its absence, there are serious (and growing) pressures to trivialize or obscure the educational experience – leading to the socially- and personally-damaging growth of fake knowledge.

Unfortunately, all too often instructors, particularly in introductory level college science courses, are not the masters of their ships; that is, they are not rewarded for generating more effective course materials. An emphasis on course “coverage” over learning, whether through peer-pressure, institutional apathy, or both, generates unnecessary obstacles to both student engagement and content mastery. To reverse the effects of the reverse DK effect, we need to encourage instructors, course designers, and departments to see the presentation of core disciplinary observations and concepts as the intellectually challenging and valuable endeavor that it is. In its absence, there are serious (and growing) pressures to trivialize or obscure the educational experience – leading to the socially- and personally-damaging growth of fake knowledge.