background: I have long been interested in students’ (and the public’s) misconceptions about biology (see this & that). More and more, it appears to me that part of the problem arises when conventional biology (and science courses in general) leave underlying scientific principles unrecognized and/or unexplained. In biology, there is a understandable temptation to present processes in simple unambiguous ways, often by ignoring the intrinsic complexity and underlying molecular scale of these systems. The result is widespread confusion among the public, a confusion often exploited by various social “influencers”, some (rather depressingly) currently in positions of power within the US.

After attending a recent Ray Troll and Kirk Johnson roadshow on fossils, art, and public engagement at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science (DMNS), I got to thinking. As a new hobby, in advance of retirement, perhaps I can work on evolving the tone of my writing to become less “academical” and more impactful, engaging, and entertaining (at least to some) while staying scientifically accurate and comprehensible. So here goes an attempt (helped out by genAI).

A common misconception, promoted by some “science popularizers” is that biological systems, including humans, are “determined” or “super-determined” (what ever that means) by various factors, particularly by the versions of genes, known as alleles, they inherited from their parents. While there is no question that biological systems are influenced and constrained by a number of factors (critical to “stay’n alive), the idea of determinism seems problematic (considered here). So where would a belief in biological determinism come from? One possibility, that emerged in the “Teaching and Learning Biology” course taught with Will Lindsay@CU Boulder, is the way basic genetics is often presented to students. The specific topic that caught my attention was the way the outcome of genetic crosses (matings) was presented, specifically through the use of what are known as Punnett’s squares.

In a typical sexually reproducing organism, the parents with different mating types or sexes, e.g. male and female, have two copies of each gene (mostly) – they are termed “diploid”. The two versions of a particular gene can be the same, in which case the organism is said to be “homozygous” or different, when it is termed “heterozygous” for that gene. The allele(s) carried by one parent can be the same or different from the allele(s) carried by the other. Molecular analysis of the alleles present in a population has been key to determining who, back in the day, was mating with Neanderthals (see wikipedia). Each gamete (egg or sperm) produced contains one or the other version of each gene – they are termed “haploid”. When sperm and egg fuse, a new diploid organism is generated.

Much of what is described above was figured out by Gregor Mendel (wikipedia). The good monk employed a few tricks that enabled him to recognize (deduce) key genetic “rules”. First, he worked with peas, Pisum sativum and related species. He used plants grown by commercial plant breeders to have specific versions of a particular trait. In his studies, he focussed on plants that displayed versions of traits that were unambiguously distinguishable from one another. Such pairs of traits are termed dichotomous; they exist in one or the other unambiguously recognizable form, without overlapping intermediates. The majority of traits are continuous rather than dichotomous.

As part of the process of generating “predictable plants”, breeders select male and female plants with the traits that they seek and discard others. After many generations the result are plants with reproducible and predictable traits. Does this mean that the plants are identical? Nope! There is still variability between individual plants of the same “strain”. For example, Mendel used strains of “tall” and “short” pea plants; the tall plants had stem lengths of between ~6 to 7 feet while the short plants had stem lengths between ~0.75 to 1.5 feet (a two-fold variation)(see Curtis, 2023). He put them into tall and short classes, ignoring these differences. But these plants were different. Such differences arise through stochastic processes and responses to developmental and environmental effects that impact height in various ways (discussed in a past post). Mendel began his studies with 22 strains of pea plants but only 7 exhibited the dichotomous behaviors he wanted. If he had included the others, it is likely he would have been confused and never would have arrived at his clean genetic rules. In fact, after he published his studies on peas, he took the advice of Carl Nägeli (see wikipedia) and began studies using Hieracium (hawkweeds), which differs in its reproductive strategy from Pisum (Nogler 2006). Nägeli’s suggestion and Mendel studies lead to uncertainty about the universality of Mendel’s rules. Mendel’s experiences reflect a key feature of scientific studies: simplify, get interpretable data, and then extend observations / systems leading to confirmation or revision.

The variation inherent in biological systems is nicely illustrated by what is (or should be) a classic study by Vogt et al (2008) who described the variations that occur within populations of genetically identical shrimp raised in identical conditions. The variation between genetically similar organisms (or identical twins) found in the wild (natural populations) is much greater. Why? because in breeder supplied plants most of the allelic variation present in the wild population is lost, discarded in the process of selecting and breeding organisms for specific traits. We see these “genetic background” effects when looking at genetically determined traits in humans as well. Consider cystic fibrous, a human genetic disease associated with the inheritance of altered versions of the CFTR gene (more on cystic fibrosis). People who inherit two disease-associated alleles of the CFTR gene develop cystic fibrosis, but as noted by Corvol et al (2015) “patients who have the same variants in CFTR exhibit substantial variation in the severity of lung disease” and this variation is associated (explained by) genetic background effects, together with stochastic effects and their developmental and environmental histories. In any of a number of studies, whenever populations of organisms are analyzed based on their genotype (which alleles they carry) the result is inevitably a distribution of responses, even when the average responses are different (for a good example see Löscher 2024).

In the case of the traits Mendel studied, he concluded that the trait was determined by the presence of different versions (alleles) of a genetic “factor”, that each organism contained two alleles, that these alleles could be the same (homozygous) or different (heterozygous), and that one allele was “dominant” to the other (“recessive”). If the dominant allele were present, it would determine the form of the trait observed. Only if both versions of the alleles present were recessive would the organism display the associated trait. The other rule was that all of the gametes produced by homozygous organism carried the same “trait-producing” allele, while heterozygous organisms produced gametes containing one or the other allele.

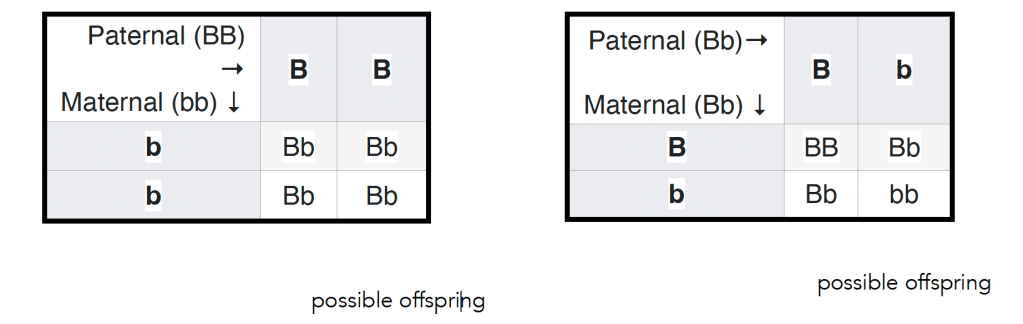

In 1905 Reginald Punnett introduced a way of thinking about Mendel’s matings, a diagram now known as a Punnett’s square (see wikipedia). In this figure (left below) ↓ the outcome of a mating between a male homozygous for a dominant allele and a female homozygous for a recessive allele is illustrated. All of the offspring will be heterozygous, but it is worth keeping in mind, however, that does not mean that they will be identical – they will display a similar level of variation in the trait seen in populations of the parental plants (see above). Again, this variation arises from the impact of environmental effects on developmental processes together with the influence of stochastic effects. The variation associated with the particular set of alleles present in an organism is captured by what is known as variable penetrance and expressivity of a gene-influenced trait (see link for molecular details). Ignoring the variations observed between organisms carrying the same allele(s) of a gene (or the same genotype in identical twins or clones can encourage or reinforce the idea that the details of an organism (its phenotype) are determined by the alleles it carries.

Another way students’ belief in genetic determinism can be reinforced is perhaps unintentional. Typically the result of the original mating between homozygous recessive and dominant parents (the P generation) is termed the first filial or F1 generation. Often the next type of genetic cross presented to students involves crossing male and female F1 individuals to produce the second filial or F2 generation (see figure – right above ↑). Such as F1 cross is predicted to produce organisms that display the dominant to recessive trait in a ratio of 3 to 1. What is often missing is that reproducible observation of this ratio requires that large numbers of F2 organisms are examined. The result of any particular F1 (heterozygous) cross is unpredictable; it can vary anywhere from 0 to 4 dominant to recessive trait displaying organisms to 4 to 0 trait dominant to recessive trait displaying organisms, and anything in between. This behavior is characteristic of a stochastic process; predictable when large numbers of events are considered and unpredictable when small numbers of events are considered. Stochastic behaviors are common in biological organisms, given the small numbers of particular molecules, and specifically particular genes, they contain (a GoldLabSymposium talk on the topic). In the context of organisms, there is room for something like “free will” (consideredhere). Whether Elon “knows” he is giving something that closely resembles a Nazi salute or not, we can presume that he is, at least partially, responsible for his actions and by implication their ramifications.

Why are the results of a mating stochastic? Because which gamete contains which trait-associated allele occurs by chance, while which gametes fuse together to produce the embryo is again a chance event. Some analyses of the numbers Mendel originally reported led to suggestions that his numbers were “too good”, and the perhaps he fudged them (for a good summary see Radick 2022). The bottom line – subsequent studies have repeatedly confirmed Mendel’s conclusions with the important caution that the link between genotype and phenotype is typically complex and does not obey strictly deterministic rules.

Nota bene: This is not mean to be a lesson in genetics; if interested in going deeper I would recommend you read Jamieson & Radick (2013) and the genetics section of biofundamentals.

Literature cited:

Corvol et al., (2015). Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies five modifier loci of lung disease severity in cystic fibrosis. Nature communications, 6, 8382.

Curtis (2023). Mendel did not study common, naturally occurring phenotypes. Journal of Genetics, 102(2), 48.

Jamieson & Radick (2013). Putting Mendel in his place: How curriculum reform in genetics and counterfactual history of science can work together. In The philosophy of biology: A companion for educators (pp. 577-595). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Löscher (2024). Of Mice and Men: The Inter-individual Variability of the Brain’s Response to Drugs. Eneuro, 11(2).

Nogler (2006). The lesser-known Mendel: his experiments on Hieracium. Genetics, 172(1), 1-6.

Radick (2022). Mendel the fraud? A social history of truth in genetics. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 93, 39-46.

van Heyningen (2024). Stochasticity in genetics and gene regulation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 379(1900), 20230476.

Vogt et al., (2008). Production of different phenotypes from the same genotype in the same environment by developmental variation. Journal of Experimental Biology, 211, 510-523.